Be a Better Writer, 2nd edition by Steve Peha, with Margot Carmichael Lester. 2016. Carrboro, NC: Teaching That Makes Sense, Inc.

Genre: Student and Teacher Resource

Levels: Steve himself says “for school, for fun, for anyone ages 10 to 16,” but honestly, you can adapt ideas in this book for just about any grade level. It would make a terrific gift for kids heading to college—and I also recommend it as a resource for adult professional writers as well as for teachers or writing coaches.

Features: Easy to use lists, charts, and techniques for handy reference; writing samples to show what works and what doesn’t—and how revision unfolds; interviews with well-known writers who offer their wisdom and suggestions; numerous activities to use on your own or in the classroom from Day 1.

Introduction

I had a hunch I would like this book as soon as I saw the cover—and no, I don’t pay any attention to that old adage. Truth is, you can tell a lot about a book by its cover. From this one with its bright colors, whimsical art, and encouraging little notes, I could tell I would be in the hands of someone who (1) probably has a sense of humor about his own writing, and (2) genuinely cares about helping writers of all ages, especially those who find writing difficult at times (and that’s most of us). Some professional resource book authors are so eager to dazzle us with their own genius that they forget how intimidating, how overwhelming writing can seem to readers. Authors with attitude always make me want to say, “Hey, pssst!! Remember us? Your audience?” After all, the underlying purpose of a resource like this should be to answer questions real writers, especially students, ask most: What should I write about? Where can I get ideas? How do I begin? How do I end? What’s a detail? How do I organize all this information I dug up in my research? Who the heck will read this and what do they care about? How do I make my writing sound more like me?

This book answers every one of these questions, and countless others—and does so in a way that makes the information entertaining as well as easy to understand and recall. It’s not a lecture; it’s a conversation. What’s more, Steve Peha and his co-author Margot Carmichael Lester (who also happens to be Steve’s wife) have gone out of their way to make sure it’s easy to find what you’re looking for—tips on sequencing, ideas for good leads, sample endings, thoughts on transitions, guidelines for solid sentences, and more. The secret lies in the layout, which is masterful. Subheads in big—really big—print, charts, lists, and other eye catching features make it easy to take in and process volumes of information. Ever go into a store that seemed to have everything you wanted, all arranged right where you could find it? That’s how it feels to read Be a Better Writer.

The book is written right to students (or any readers looking for guidance on writing well) in a voice that’s friendly, often humorous, and always knowing. You can tell immediately that these are seasoned writers, that everything you struggle with they’ve struggled with, too. Steve is refreshingly honest about his own learning curve: “I know that for some of us, writing is hard. That’s how it was for me in school. I was good at math. I could read. But writing was a mystery, one I didn’t solve until I started helping other people solve it for themselves” (p. 4). Someone who’s fought his own writing demons gives good advice because he knows exactly what advice we’re most likely to need, from topic choice right down to dealing with those pesky commas. Steve and Margot know their stuff, and know how to make a book on writing fun to read.

I sat down with this book intending to read a sample chapter or two, and was immediately delighted to have the author tell me two things I never expected to hear: (1) You don’t have to read this whole book, and (2) You don’t have to read it in order. I don’t? Gee . . . It’s always a relief to get permission for something you were probably going to do anyway—like skim. While savoring this newfound freedom, I actually did read the whole book—all of it, in order, and in one sitting. Yes, it was that good. Yes, it was that engaging. And yes, you are going to love it, too.

Everything That Matters

Too many resource books try to cover everything. I have a few of those. They’re too big to lift, but ideal for door stops. This book thankfully takes a more discretionary approach. It concentrates, very effectively, on “what matters most.”

In the opening chapter, Steve gives us a stunning “world of writing” overview. He writes about logic, good beginnings, effective description, using easy techniques to get yourself moving when you’re stuck, applying the ingenious “what-why-how” strategy when writing an essay test, getting and using good feedback, and ways to know when you’re finished writing: in short, the “most important” issues writers encounter in their everyday lives. This big picture chapter provides the foundation for the enormously rich discussions that follow, but equally important, it offers a beginning writer assurance: Yes, you can do this. Even if you learn and use just three or four strategies from this book, Steve tells us, you’ll be a better writer. Three or four? you say to yourself—Heck, I can do that! Yes, you can, and now you’ve grasped the underlying theme of the book: making writing do-able, one strategy at a time.

The Top 10. That first chapter and all others open with what is hands down my favorite feature: “10 Things You Need to Know Even If You Don’t Read This Chapter.” I’m certain—I’d bet on it—that you can name six writers right off the top of your head that you wish had used that approach. The “10 Things You Need to Know” opener works on so many levels. First, it gives me a quick preview of the upcoming chapter—which makes my reading infinitely more efficient. Second, it allows me to focus on the sub-topics I need most. And finally, it gives me a simple way to review later so I can recall key points or look something up.

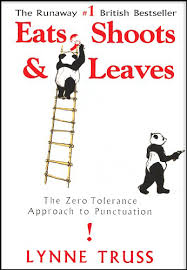

Targeting good writing. Six of the other eight chapters cover topics that define the heart of good writing: “Better Topics,” “Better Ideas,” “Better Organization,” “Better Voice,” “Better Words,” and “Better Sentences.” The book doesn’t cover everything you ever wanted to know about conventions plus a few things you didn’t (just one more thing to love about it), but does offer excellent chapter on “Better Punctuation” that also includes an editorial nod to paragraphing and capitalization. Steve, with his characteristic sense of humor, has a good time showing how punctuation can alter meaning in even a short sentence like Herman Melville’s classic opening line from Moby Dick, “Call me Ishmael.” (Think about it until you get your own copy; try punctuating it as many ways as you can.)

I cannot say whether this was intentional (and it doesn’t matter), but Be a Better Writer is extremely “trait friendly.” If you teach the six traits to your students, you will find this book filled with activities you can use for that purpose. But wait, there’s more . . .

The book also devotes a whole chapter to “Better Fiction,” so just in case you’re reading it not so much to teach writing as to get your own work published, here’s a chapter you’ll savor—and if you’re like me, it will have you rolling up your sleeves and revising in your head even before you finish reading it.

Organization Plus

The book is beautifully organized, and next to the confident, upbeat voice, this is the characteristic I appreciated most. The pacing is quick and lively, and chapters include recurring features that I quickly learned to look for, like these five:

Feature 1: Terrific checklists. Every chapter features an enormously useful checklist related to the subject at hand. For example, Chapter Two offers us “Your Checklist for Better Topics.” Like most writers, I am constantly in search of a good topic, so I devoured this list. Steve is particularly good at coming up with questions students can ask themselves and he embeds these into the checklist: “What ideas and details will encourage readers to follow my piece all the way to the end? What will make them feel like it was worth the time and effort they get to spend there?” (p. 35) Questions like these remind me that writing well requires us not only to think like readers but to offer our audience something in return for the gift of their time and commitment.

Feature 2: Samples—and lessons in modeling. Each chapter includes one or more writing examples, some written by Steve and many written by students. In this chapter, Steve uses a piece of his own writing, titled “My Father’s Gift,” to illustrate the difficulties inherent in “Tackling Tough Topics,” things that are just plain hard to write about because our emotions get in the way. He helps us understand how pushing ourselves into topics that make us uncomfortable forces us to learn new skills and sharpen old ones. Here’s a quick summary of Steve’s story:

Steve’s father, a man without a lot of money to spend, has given 10-year-old Steve a gift in a manila envelope, and waits eagerly for his son to open it. They are not close, and there’s a palpable tension between them. Days go by, and Steve still has not opened the gift, so has to lie when his father questions him about it. When he finally does look inside, he discovers that the envelope contains valuable photographs of his favorite team, the Washington Huskies. Even though he likes and appreciates the photos, he doesn’t safeguard them, nor does he fully acknowledge the value of the gift. Years later, needing to raise money in a hurry, he remembers the photos and decides to sell them—only to discover he has inadvertently sent them off with the trash while cleaning out his room. Realizing what he has done, and imagining how his father would react if he knew, sets off a chain of conflicting emotions that make this story of giving and receiving hard to resolve—but Steve writes a strong ending about “where giving and forgiving meet, and grace abides” (p. 52).

When I show teachers how to model writing, I encourage them to do something that doesn’t come easily to most: to think out loud, sharing the way writing unfolds in the writer’s mind. Students need to know why we begin or end a certain way, why we add a phrase or delete a word. Most teachers understand this instinctively, but somehow the act of actually sharing their thinking aloud with students feels awkward, and makes many self-conscious. That’s why I wanted to cheer when I finished the story and then read Steve’s description of his own writing process. It’s precisely the kind of sharing that helps kids understand how writing works: “I had an easy time with the beginning,” he reveals, “but it took many tries to write the ending” (p 35). He explains that he had to realize his story was about forgiveness before he could get the ending right. “When I was thinking only about the fact that my piece needed an ending, I wrote many endings, but never one that captured what I wanted to say because I hadn’t thought at all about what that was.”

There are two lessons here: One, an ending needs a message. And two, students learn so much by getting inside a working writer’s head. This book takes them there—to where the writing happens. I cannot think of another writing resource book that does this so well.

Feature 3: The Unexpected. Everyone loves surprises, and Be a Better Writer delivers. Though it has recurring features, it’s never formulaic. Chapter Two, for instance, includes a section that made me sit up and take notice: “Topic Choice When You Have No Choice.” Think “on-demand writing.”

Back in the day, when my writing assessment team and I were reading literally thousands of stories and essays for county, district, and state writing assessments, all of us wondered how it could be that though students were often writing to the very same prompt, some managed to make their writing irresistibly engaging, read-out-loud funny, or heart stoppingly moving, while others were clearly so bored it was a wonder they could push their pencils across the paper. The secret lies in learning to personalize a topic. How does a writer do that?

Try Steve’s “Topic Equation Strategy,” in which Interest + Subject = Topic. Without giving away too much of Steve’s thunder, let me say that this equation simply calls for coupling your assigned subject—say it’s climate change—with something that interests you, like whales, perhaps. Instead of writing in a broad brushstroke kind of way about climate change, you might ask, How is climate change affecting whales, and will they survive it? Will warming ocean waters disturb their migration cycle, and what will they eat if all the krill die? Now you have a topic that will keep both you and your readers awake. Solving a problem (e.g., the dreaded assigned topic) that has plagued students and teachers for generations is a stroke of genius, and for me, this solution alone makes the book worth its purchase price.

Feature 4: Interviews. Among the book’s most intriguing features are interviews with various writers of note who talk about how they became writers and offer advice to beginners in the craft. The authors chose their interviewees well; each has something memorable to say. Among my favorite moments are these lines from Luis J. Rodriguez, known for his books of memoir, fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and children’s literature. Asked why he writes, Rodriguez says, “To heal. To dance. To wake up something beastly as well as something beautiful. I write to stay alive.”

Feature 5: Activities, activities. All chapters wrap up with a list of activities you can try (as a student, or as a teacher/coach working with students), and they range from easy to challenging, quick to extended. Sometimes Steve invites us to journal a character or try transforming a telling statement to a showing one, and other times we’re asked to write a letter, experiment with organization, collect beginnings and endings, or write a piece in a whole new voice. What makes these activities so authentic and appealing is that they’re things Steve himself has tried as a writer. And as he reminds us at the beginning of the book, we do not have to do all the activities. We can pick and choose. But this is guaranteed: If we do enough of them, our writing will improve.

Miss Margot’s Role

Co-author Margot Carmichael Lester is a journalist and author. She offers her journalist’s perspective throughout the book, and it’s a great balance because by her own admission, she leans toward nonfiction and opinion writing. Like all good journalists, she knows the value of writing concisely and cutting what isn’t needed. Though she offers us many good pieces of advice throughout the book, I think this one has to be my favorite: “When I have too many details, I re-evaluate them. If a detail doesn’t support the main idea, it’s out. If it doesn’t lead people to think feel, or do what I want them to, it’s gone. If it doesn’t answer a critical question or objection from the reader, it’s toast.” I love a ruthless editor, and ruthlessness is a quality more students need to cultivate as writers. Hack away, Miss Margot (p. 73).

Hidden Gems

You may have noticed that you can always tell which resource books were worth your while because the best ones are eventually filled with highlighted passages and raggedy sticky notes. That’s because readers have highlighted, circled, underlined, and commented on the book’s hidden gems, little bits of wisdom that aren’t paraded before us in any obvious way, but just wait there tucked inside the folds of text, waiting to be discovered. Here are just a handful of the quotable moments I noticed while reading Be a Better Writer. Have a highlighter and pencil handy when you read your own copy because you will find many more moments like these:

- “The key to descriptive writing is making a picture in your mind and using words and phrases that help readers make the same picture in theirs” (p. 11).

- “Getting feedback isn’t just finding out why some people like your writing and others don’t. It’s about getting precise information about how to improve your work” (p. 27).

- “Life experience is the greatest source of topic ideas you’ll ever have” (p. 33).

- “Think of your teachers as editors” (p. 36).

- “If you’re like many writers, you’ll come back to the same topics again and again” (p. 57).

- “Voice is the most important quality in your work because it influences all of the other qualities” (p. 157).

- “Draft like you talk and revise like you read” (p. 189)

Not surprisingly, Be a Better Writer has enjoyed overwhelming popularity since its release. If you’d like a copy of your own or want more information, here are some links that will help:

To get the book on Amazon:

To get a free PDF copy of Chapter 1:

To see Steve’s newsletter:

http://bit.ly/steve-peha-newsletter

To visit Steve’s Author Central Page on Amazon:

http://bit.ly/babw-amazon-author-page

Steve and Margot are offering a huge discount (40%) thru June 30 for schools ordering 25+ copies by PO.

http://bit.ly/babw-po-discount

Jeff and I say goodbye for the summer–just for the summer!!

Thank you for returning—and for recommending our site to friends. We have gained many new fans over recent months, and we have you to thank! Like many of you, Jeff and I are going to take a summer break to do some traveling and spend time with our families. We will return in the fall with more reviews and thoughts about teaching writing well. Writing isn’t just our occupation—it’s our passion. Remember, for the BEST workshops or innovative classroom demo lessons combining traits, workshop, process and literature, please phone Jeff at 503-579-3034. Give every child a voice.