I’m ever so happy to let you know that my first work of fiction, No Ordinary Cat, is now available through Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/No-Ordinary-Cat-Vicki-Spandel/dp/0997283130

It’s been quite a journey! It began about three years ago, when a gorgeous feral cat showed up in our yard, and I couldn’t stop staring at him through the window. He was curious, but wary, with the most beautiful face and highly intelligent eyes. I couldn’t help wondering where in the world he’d come from. We live in a rural area that’s almost uninhabited in winter, so he had to have traveled a long way to reach our yard. Through the snow, no less. Dodging predators every inch of the way. Puzzling over his story prompted me to write about a cat who is itching to explore the world—and finds a bit more than he’d bargained for. I had no idea it would turn into a book, and that took a couple of years, but what an adventure it’s been. And what an education. It has taught me profound respect for people who write fiction. It is more difficult and more complex than nonfiction. Because, my word, you have to make every last bit of it up!

Cats—and Wilderness

I love cats. They’re fiercely independent and can amuse themselves for hours. They’re incredibly entertaining to watch, partly because some part of them remains wild, and this shows up in a hundred ways—in how they comport themselves, how they stalk anything from mice to spiders to feather toys, and even in how watchful and alert they are. So, writing about cats came naturally—but the cat characters in my book are mostly invented. I did have cats once, Silver Tipped Persians. Gorgeous and very haughty. One, Suki, was brainy as all get-out, while the other, Zoey, could barely recall where the food was. My cats have cameo appearances in the book as Sadie and Karma. Sadie dares Rufus to make a journey he is completely unprepared for—and that would definitely be a stunt Suki would have pulled.

Rufus, the main character, has a tad of wildness in him, but is basically a home body, who loves evenings on the hearth, delicious food—and humans. To show the wild side of cats, I needed a counterpart. That’s Asha, who is wild through and through.

I hoped through Asha to shine a spotlight on the plight of feral cats. Scientists estimate we have somewhere between 60 and 120 million feral cats in the U.S., with Vermont apparently having the highest population. This surprises me since although Vermont is largely wilderness, it’s also very cold in the winter, so one would think it would be an inhospitable environment for an animal without shelter.

Feral cats do not live long lives. Life is hard when you have to hunt for every meal and search out shelter constantly. Feral cats are not much loved by humans because they do carry disease and they kill millions of song birds annually. So they’re often mistreated, but these days, there are agencies that offer help. Look up “help for feral cats” to find one in your area.

Most feral cats die of disease or are killed by wild animals. The forests and wetlands surrounding my home (the basis for the wilderness in the book) are inhabited by coyotes, badgers, bobcats, raccoons, and a few mountain lions—any of which can easily kill a cat. Of course, feral cats become pretty wily over time, and are less likely to be killed by such animals than are domestic cats. Pets disappear in our neighborhood constantly. I am forever warning visitors from Portland and Eugene not to let their dogs (or cats) roam free at night, but sadly, many do not take this warning seriously—and pets are lost hereabouts routinely. One man told me the deer would be wise to watch out for his Lab. Actually, it’s the other way around. Deer are not predators, but they are more than capable of defending themselves, and a Lab is no match for a riled deer.

In No Ordinary Cat, I tried to create a wilderness that is realistic. Beautiful and almost irresistibly alluring, but yes, sometimes dangerous. Asha manages to navigate this wilderness quite well, but for Rufus, the threat of death lurks around every shrub. He is not a born hunter. Some cats simply aren’t. This is what makes his personal journey so interesting, though. If he were simply visiting the next-door neighbors, we wouldn’t need to worry about him. And worrying about the main character is part of the fun in reading, don’t you think? I didn’t in any way intend to make the book dark and gloomy. Risk is just part of life in the wilderness—and wilderness is part of what the book is about. It’s about much more, though.

Loneliness, Friendship, and Heroism

When I began writing this book, I envisioned it as a children’s chapter book, an adventure story in which a cat gets out of his depth but is eventually rescued. It turned into something very different.

As you write about characters—and keep in mind that I worked on this book for a couple years—their personalities grow and expand and change. At first, Rufus was a tenacious, ambitious little kitten who just wanted to get away from home and see what the world was about. He was, in other words, like most young humans.

But as I wrote about him each day, he evolved into something more. A character with heart. Compassion. Intuition. He was capable of sensing loneliness in others—and he had the power to do something about it. This is not a fantasy, actually. Many animals are intuitive in this way, and it’s part of what we love about them.

During this crazy time in which we live, loneliness is something we all deal with. We can’t hug our kids unless they are young enough to live with us. Mine aren’t. We can’t have friends to dinner or go to parties. Yes, we can go on walks and wave at a distance. Yes, we can have people come to the back yard and sit six feet from us. But the heart yearns for more.

Mr. Peabody the poet and Mrs. Lin the gardener, the two human characters in the book, each live alone. This was a purposeful choice on my part. I know—or have known—many people who live alone, and it takes great strength. Courage. Like all of us, these people need love and companionship. Wouldn’t it be wonderful, I thought, if Rufus turned out to be more than a “pet,” a term I don’t use in the book because the animals in this book are friends. What if he were a true companion, a soulmate? I’m not going to say I made him this because writing doesn’t work like that. I allowed him to become what he needed to be—and he is, I think, a character for this time, a mender of hearts. He’s the friend you long for when you’re isolated, apart from those you love and miss.

If you’ve had an animal—dog, cat, horse, donkey, or something else—to whom you’ve felt close, I think you will feel this sort of connection with Rufus, and see him as the hero he truly is.

A Word About Revision

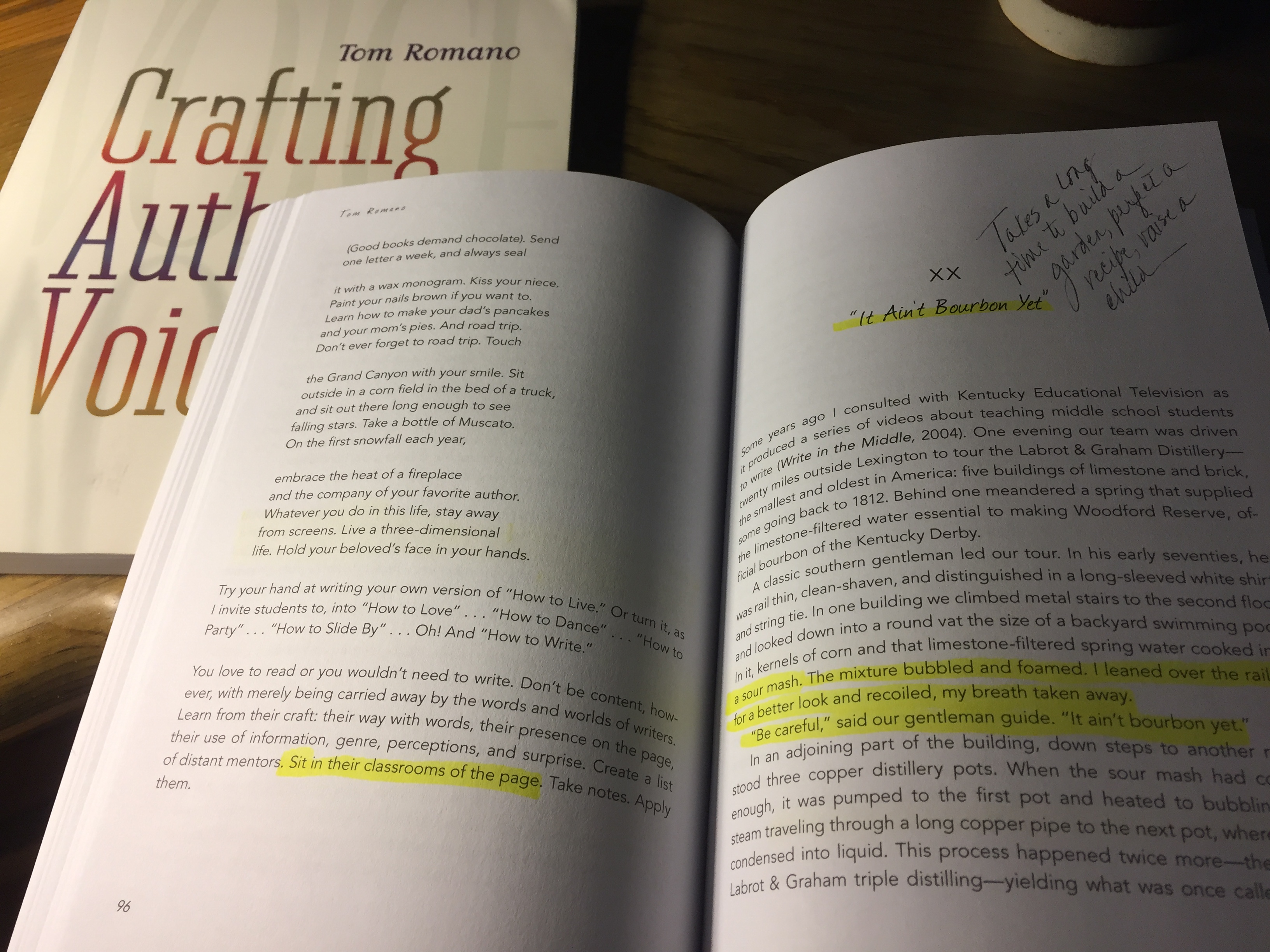

I learned worlds about revision writing this book—and would never teach it the same way again.

Writing instruction starts, I think, with helping people find what they have to say. Then listening when they say it. It also means teaching people how to revise their work—and this is where so much of our instruction breaks down. And I speak for myself here too because although I imagined myself doing the right things—forming writing groups, holding conferences—I wasn’t ever sure I was teaching revision. I was promoting it, that’s for sure. Encouraging it. Requiring it, even. But none of that is teaching. We really do need to show students what it looks like. How we might have an internal debate about the use of a single word. For example, toward the end of the book, I refer to Rufus as Mr. Peabody’s writing “cohort.” No big deal, right? Yes, for me, it was. The word had to convey the right meaning and feeling, and I changed it many times. Writing buddy? Warm, but not respectful enough. Writing assistant? Inaccurate, and too businesslike. Rufus wouldn’t work in an office. Writing companion? Close, but not quite it. Rufus was more than that. His presence actually energized the poet to write. If you’ve got a cat on your desk, you know what I mean. Writing conspirator? Definitely a good option—but just a tad too shady. Writing cohort? Perfect.

I could take any number of paragraphs from the book and show how they evolved over time through revision. I’d love to do a slow-mo film of this very thing. I’d loved to show students how many lines I deleted. Probably half the original book. Students are often reluctant to hack off whole sections of things they’ve written. It’s so hard to get it on the page in the first place! But the more you do this, the better it feels, and of course (usually), the better the writing gets.

I’ve read countless books on writing instruction that describe why revision is important, and they usually say something I’ve always considered kind of condescending, something like, “Nobody gets it right the first time.” They mean, I think, that it’s hard to transfer thought to paper. That’s true. We don’t think just in words, after all, but words are all we have to capture impressions, feelings, images, sensory details—all of it. Think how challenging that is.

In addition, though, revision isn’t really about getting it “right.” The premise is wrong here. There isn’t some “right” thought lurking in our brains that we just have to dig and sweat to uncover. Writing doesn’t work like that at all. What happens is, the message grows, expands, shapeshifts, and refines itself in your head as you write. Writing and thinking are symbiotic. Each requires the other and feeds the other.

The other thing I’d do differently is help students understand how much time revision takes. Even if I couldn’t provide them enough time, I’d want them to know this. In school, most of the time, so-called revision is an imitation of the real deal.

Writing a passage (paragraph, story, report, whatever) and then going back to “revise” it is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s revision, yes—but in the sense that having a stalk of celery before a meal is eating. True revision takes multiple readings—and living with a piece for a while, thinking about it while you’re walking, gardening, eating, cleaning, trying to go to sleep. Imagining possibilities, asking “What if?” kinds of questions: What if Rufus ran away from home? What if he were killed—or almost killed? What if someone rescued him? What if he didn’t go back—but decided to live with his rescuer?

The logistics and practicalities of the classroom (or virtual classroom, these days) make it hard to give students weeks or months to “live with” and work on a single piece of writing. But they could watch us go through a single piece. We could share updates with them, ask them to be a writing group for us, asking questions and suggesting possibilities. Then they could at least witness revision.

While we’re at it, we could teach students to ask really good questions, the kind that push a narrative forward. The best feedback doesn’t come at the end of the writing but while a writer is working on something. That’s when you can have a real conversation. Revision is sparked by questions like these:

- What’s happening with your story? Is it changing? How?

- What are you struggling with right now?

- What do you do when you can’t think where the plot takes you next?

- Are your characters morally good? What makes you think so?

- What if you changed the setting—to, say, London? What else would change?

- Who do you picture or hear reading this? Could this be an audio book?

- Do you have an ending in mind—or do you think the ending will surprise you?

- Are you directing the characters? Or do you feel as if they’re making their own decisions?

- If this book became a film, how would you cast it?

Too often students think of revision as drudgery. Let’s bring some fun back into it. I must say—and I would tell this to students if I were fortunate enough to have any right now—I had one heck of a good time revising this book. Of course, I made it fun for myself. I kept my revision time to 3-4 hours a day. I sit where I can look out at the trees and sky. I started with a cup of coffee, fresh ground, with almond milk. I played music. For this book, the sound track (and you really should look this up—it’s spectacular) is Hennie Bekker’s African Tapestry. I played it repeatedly. This is the music that takes Rufus over the meadow at sunset and into his new life. It’s the music that leads Asha on her adventure with the Golden Eagle. It’s the music that will forever play in my heart as the theme of revision.

Who Should Read This Book?

Everyone! Ha, ha. Well, that would be lovely, but let’s be realistic.

I’ve never really been partial to reviews that tell you a book is for a certain age—“Recommended for ages 10 to 13.” Who says?

So—while this started in my mind as a book for young readers, I think it’s really a book for anyone of any age who loves cats or treasures friendship or thinks animal friends can do as much as human friends to cheer and emotionally rescue us, especially now.

It’s a warm, friendly, curl up by the fire kind of book. It does reveal the dark side of nature, that’s true, but it also shows the power of love and friendship, which is, I think, its main theme. I came to really like my characters as I wrote about them. I love Asha for her courage, her spirit, her determination to live life on her own terms. If a cat can be a feminist, Asha is such a cat. And I love Rufus for his sensitivity, his openness to new adventures, new experiences, and new friends. His capacity for love is infinite.

Some Thanks Are in Order!

It takes more than one person to build a book.

Steve Peha. I definitely want to thank my writing coach, designer, and publisher, Steve Peha. Steve was the first person to read the book and he immediately encouraged me to finish it and publish it. His enthusiasm was infectious. His comments and questions along the way were invaluable in fleshing out the characters, shaping the plot, and enriching the story with a touch of philosophy, something I wanted it to have.

I don’t want to pass too quickly over the design part of Steve’s contribution, either, because to me, this was a BIG deal. I love square books, and Steve liked the idea of making the book square. I’m inevitably drawn to square books any time I visit a book store. If you buy a copy of my book, see if you don’t love holding a book this size in your hands. It just feels so—right. You’ll also notice how enormous the cat face is on the cover. Can you even look away? Those mesmerizing eyes say this cat has a history. He’s had some adventures and gained some wisdom. He’s someone you ought to know. Well done, Steve.

The inside illustrations fill whole pages also—as they should. They’re frame-worthy and essential elements of the story that need their own space.

I’m also fond of the gold print Steve chose for the title. It’s striking and picks up the gold in Rufus’s eyes.

Look inside and immediately you’ll notice those enormous margins. It’s inviting to open a book that doesn’t bombard you with print. Big margins welcome you. You want to step inside, and you may think to yourself, “This feels good. This is a book I can conquer. It respects readers and wants them to be comfortable.” I hope that’s just how you feel when you read it. Comfortable. Welcome. As if I’d been thinking of you when I wrote it.

Steve Peha, by the way, is a gifted writing consultant and outstanding coach, author of the bestselling book Be a Better Writer (also available on Amazon). You can email him at stevepeha@gmail.com

Jeni Kelleher. Special thanks to my stunningly talented illustrator, Jeni Kelleher. Jeni literally poured her heart and soul into making the characters in the book come alive, and the results are hauntingly beautiful. Rufus is charming as a kitten and gorgeous as an adult. Asha is as mysterious and ominous as she needs to be. Her face at the end of the story, peering out from the dark, is among my favorites.

In the book, I’ve written a brief story of how Jeni and I met. It was fate, kismet, whatever name you wish to put on it. I met Jeni in a coffee shop I’d never visited before, on a day when she just happened to be featuring her art on the coffee shop wall. And just happened to come in. How many coincidences do you need to create good fortune? I cannot believe I found this person who told me that day, “I always begin my paintings with the eyes. Eyes reveal everything.” In my story, eyes are crucial. They tell all there is to know about the characters. I could not possibly have found a better artist. Jeni specializes in animal portraits, and you can reach her at petportraitsbyjeni.com

Darle Fearl, Jeff Hicks, Leila Naka. And now for a few people who won’t expect to be mentioned. As I was writing this book, I “played” several voices in my head, having them read aloud to me. I didn’t have a writing group at the time, so I had to be inventive. The two voices I kept circling back to belonged to my wonderful six-trait buddies and writing cohorts, Darle Fearl and Jeff Hicks. Both are teachers. Jeff is also a writer, and has collaborated with me on countless educational materials published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. But what’s most important here is that they both read with such expression, such sensitivity, that as you’re listening you think, “If I ever do an audio book, I hope you’re the reader!”

Listening to these two masterful readers in my head, even though it wasn’t live, was invaluable in helping me with revision—especially voice, dialogue, and rhythm. If a book doesn’t engage you when you hear it aloud, you sure as heck won’t enjoy reading it silently. I wanted this one to be one you could read aloud to a child, a friend, or just to yourself, and have a rollicking good time doing that. I hope it turned out that way.

And finally, mahalo to my dear friend Leila Naka. Remember that night so long, long ago when we had dinner in Chicago after the boat tour through the city’s memorable architecture? What a day! You kept telling me, “You need to write a book! I love your emails! Write a book!” Should everyone who writes appreciated emails write a book? Beats me. But I decided to believe you, Leila, and give it a shot. So this book is partly your doing. Your voice has been in my head for a long time nudging me along. Thank you for believing. All great teachers are believers. I do so hope you love the result.

Thank you also to my friends who so generously agreed to review the book for me. Your copies are in the mail! You are all so deeply appreciated.

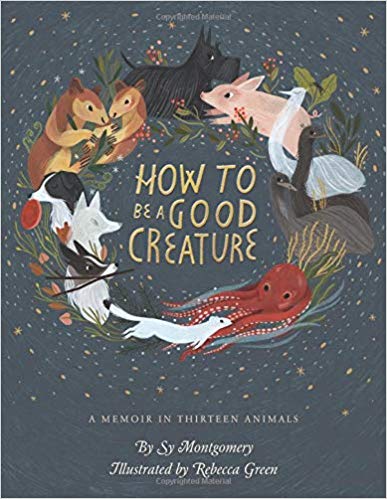

I have loved many books, but none will ever replace this one in my heart. Now and again, a book speaks to you on such a deep level that you feel an immediate bond with the author, feel changed for having read it, and know you will return to it again and again. How to Be a Good Creature is a book to treasure, one to give to those you love. Initially, in fact, I did buy it as a gift. As an avid reader, though, I couldn’t resist one small peek (You know how it is), and after only a couple pages I couldn’t put it down. I knew right then I’d have to not only keep that copy forever, but buy several more—for this is a book that begs to be shared.

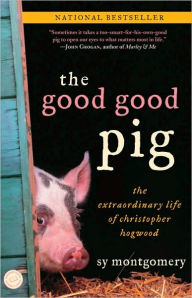

I have loved many books, but none will ever replace this one in my heart. Now and again, a book speaks to you on such a deep level that you feel an immediate bond with the author, feel changed for having read it, and know you will return to it again and again. How to Be a Good Creature is a book to treasure, one to give to those you love. Initially, in fact, I did buy it as a gift. As an avid reader, though, I couldn’t resist one small peek (You know how it is), and after only a couple pages I couldn’t put it down. I knew right then I’d have to not only keep that copy forever, but buy several more—for this is a book that begs to be shared. In part, I suppose, this is because I already knew Christopher. Though I never had the honor of meeting him personally, I have been a stalwart member of his fan club for years. I carried Sy’s book The Good Good Pig for thousands of miles, reading from it to teachers in writing workshops everywhere—and always giving the copy I’d brought to someone in attendance. I think The Good Good Pig was my favorite of Montgomery’s remarkable books (though Birdology and The Soul of an Octopus competed feverishly for my heart) until this current little gem came out.

In part, I suppose, this is because I already knew Christopher. Though I never had the honor of meeting him personally, I have been a stalwart member of his fan club for years. I carried Sy’s book The Good Good Pig for thousands of miles, reading from it to teachers in writing workshops everywhere—and always giving the copy I’d brought to someone in attendance. I think The Good Good Pig was my favorite of Montgomery’s remarkable books (though Birdology and The Soul of an Octopus competed feverishly for my heart) until this current little gem came out. Happy as I was to hear more about Christopher, though, here’s what really struck me: In this third chapter, Sy makes clear that she doesn’t just find animals interesting. She doesn’t just observe or study them. Her feelings soar far beyond empathy. To be sure, she rescues animals in need (a lifelong enterprise), and Christopher Hogwood is one beneficiary of her boundless sensitivity. But these animals are more than pets or companions. They are her friends—in every sense of that word, and with all that friendship implies. Somehow, her capacity to understand them, and to get inside their minds and hearts, creates a species-to-species rapport that bypasses all limitations. Love at this level is transformative, both for Sy and for us as readers. Countless humans (you may be one) have bonded with dogs, cats, or horses. But do you know many who’ve experienced true friendship with, say, a tarantula? Or an octopus?

Happy as I was to hear more about Christopher, though, here’s what really struck me: In this third chapter, Sy makes clear that she doesn’t just find animals interesting. She doesn’t just observe or study them. Her feelings soar far beyond empathy. To be sure, she rescues animals in need (a lifelong enterprise), and Christopher Hogwood is one beneficiary of her boundless sensitivity. But these animals are more than pets or companions. They are her friends—in every sense of that word, and with all that friendship implies. Somehow, her capacity to understand them, and to get inside their minds and hearts, creates a species-to-species rapport that bypasses all limitations. Love at this level is transformative, both for Sy and for us as readers. Countless humans (you may be one) have bonded with dogs, cats, or horses. But do you know many who’ve experienced true friendship with, say, a tarantula? Or an octopus? The differences between Sy and Christopher—he’s a quadruped, she’s a biped, he has hooves and she doesn’t—will not “trouble” their relationship, she tells us (the way smaller differences have bungled her relationships with humans). How could they? She recognizes in Christopher a genuine spiritual capacity to love and to teach others about love. He’s a pig, yes, but that’s only physical. He’s also the “great big Buddha master.” In what is surely one of my favorite lines from the book, Sy declares, “ . . . Christopher helped create for me a real family—a family made not from genes, not from blood, but from love.”

The differences between Sy and Christopher—he’s a quadruped, she’s a biped, he has hooves and she doesn’t—will not “trouble” their relationship, she tells us (the way smaller differences have bungled her relationships with humans). How could they? She recognizes in Christopher a genuine spiritual capacity to love and to teach others about love. He’s a pig, yes, but that’s only physical. He’s also the “great big Buddha master.” In what is surely one of my favorite lines from the book, Sy declares, “ . . . Christopher helped create for me a real family—a family made not from genes, not from blood, but from love.”

![The Promise Between Us by [White, Barbara Claypole]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/61lTvP1eUGL.jpg)

As humans, we’ve likely pondered the possibility of alien life since we first looked up at the stars. Now we might be close to answering the question meaningfully, making this—from a scientific perspective—one of the most exciting times to be alive. Ever.

As humans, we’ve likely pondered the possibility of alien life since we first looked up at the stars. Now we might be close to answering the question meaningfully, making this—from a scientific perspective—one of the most exciting times to be alive. Ever. I’m a long-time fan of Seymour Simon’s nonfiction, and have carried his books to countless workshops, sharing them with teachers and students alike—who always madly scribble down titles. Special favorites for me include Big Cats, Animals Nobody Loves, Gorillas, Sharks, Whales, The Brain, The Heart, and Our Solar System, but let me just say that you could read all day and into tomorrow, and still have numerous remarkable Seymour Simon books to explore. As a former teacher, Simon knows how to engage students, how to emphasize important details, how to get conversationally technical without drowning us in hard-to-recall statistics, and above all, how to suggest stimulating questions and issues for us to think about.

I’m a long-time fan of Seymour Simon’s nonfiction, and have carried his books to countless workshops, sharing them with teachers and students alike—who always madly scribble down titles. Special favorites for me include Big Cats, Animals Nobody Loves, Gorillas, Sharks, Whales, The Brain, The Heart, and Our Solar System, but let me just say that you could read all day and into tomorrow, and still have numerous remarkable Seymour Simon books to explore. As a former teacher, Simon knows how to engage students, how to emphasize important details, how to get conversationally technical without drowning us in hard-to-recall statistics, and above all, how to suggest stimulating questions and issues for us to think about.

Background. How many of your students have wondered about the possibility of life on other planets? Or wondered how many other planets there might be in the universe—or just within our own Milky Way galaxy? For fun, have students write short paragraphs about this, speculating or offering their current beliefs. After sharing selected passages from the book, talk about whether their ideas have changed—or their beliefs have been reinforced. Share your own thoughts, too–with, of course, the caveat that no one knows the answer to this question. Yet.

Background. How many of your students have wondered about the possibility of life on other planets? Or wondered how many other planets there might be in the universe—or just within our own Milky Way galaxy? For fun, have students write short paragraphs about this, speculating or offering their current beliefs. After sharing selected passages from the book, talk about whether their ideas have changed—or their beliefs have been reinforced. Share your own thoughts, too–with, of course, the caveat that no one knows the answer to this question. Yet. You might also wish to ask students how many have seen films or read books that explore the idea of alien life. What forms does that fictional life usually take? Do they feel these portrayals are realistic—or mostly a product of writers’ and film makers’ imaginations?

You might also wish to ask students how many have seen films or read books that explore the idea of alien life. What forms does that fictional life usually take? Do they feel these portrayals are realistic—or mostly a product of writers’ and film makers’ imaginations? Note: In his famous book Cosmos, astronomer Carl Sagan wrote this:

Note: In his famous book Cosmos, astronomer Carl Sagan wrote this:

Are your students writing their own nonfiction? Let us help!

Are your students writing their own nonfiction? Let us help!

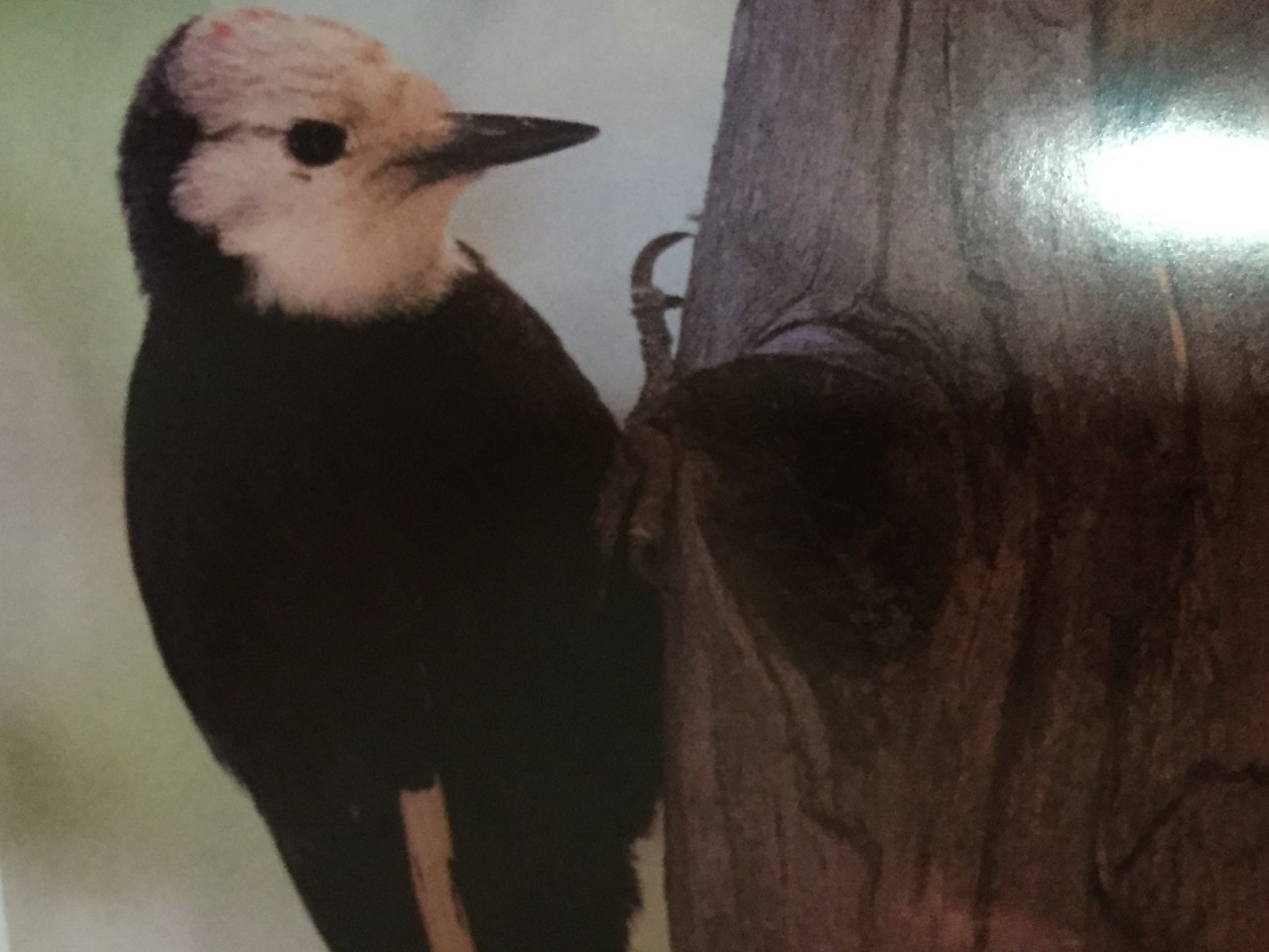

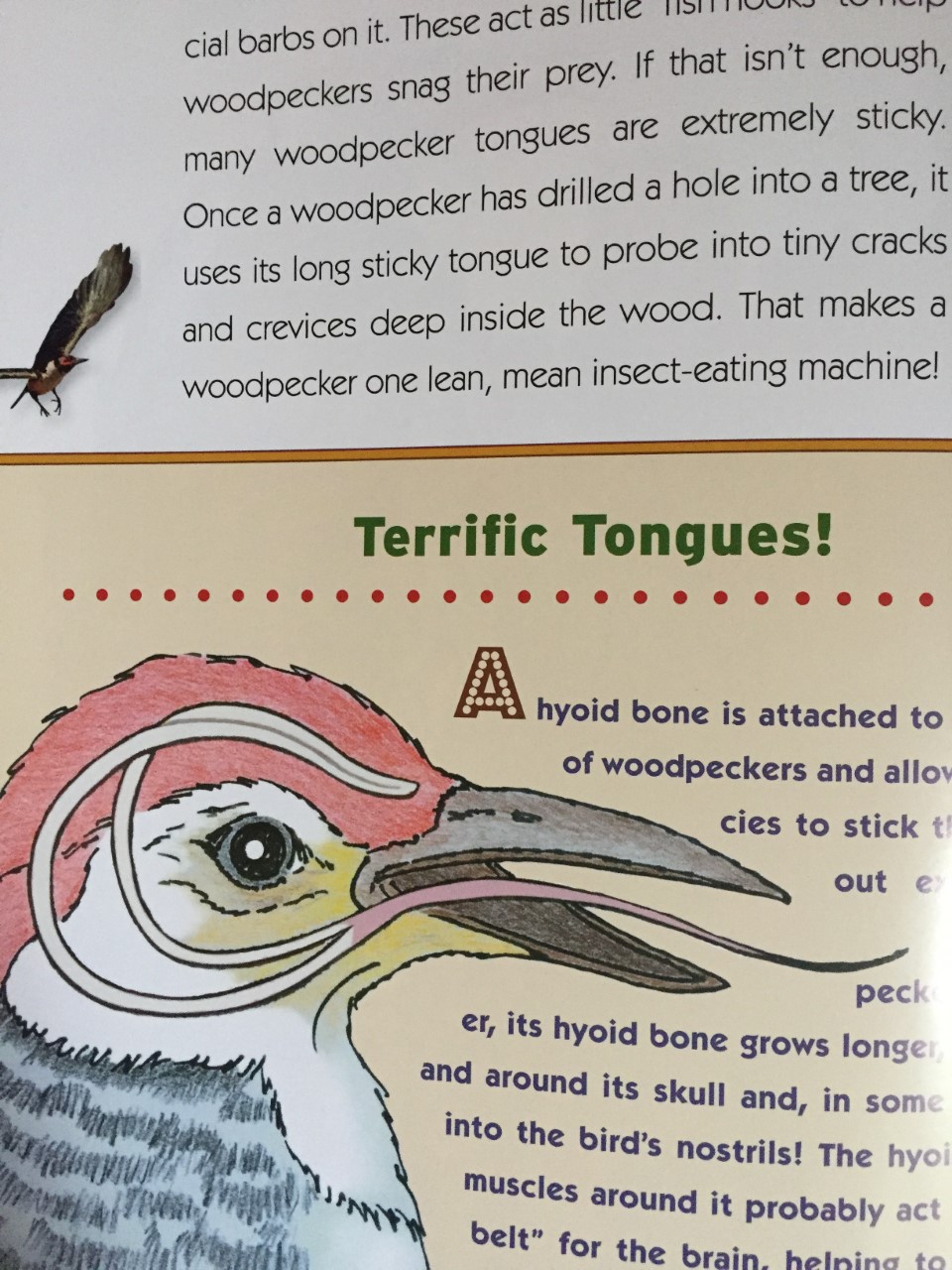

Even after roughing out that approach, however, I made dramatic revisions. One was to seek out and add quotes by woodpecker experts. Another was to axe my introduction. At first, I had recounted my experience with Acorn Woodpeckers. That intro was okay, but I decided that it didn’t really add to the book, so out it went! What might be readers’ favorite feature of the book, the “Photo Bloopers” spread, was a last-minute addition. I was lamenting our failure at getting really great Arizona Woodpecker photos and just decided, “Well, what if I just put these imperfect photos in and call attention to the fact that we tried—and failed—at photographing these uncooperative critters?” That turned out to be a terrific revision. Besides the above points, I went through countless rounds of tightening, recasting, replacing verbs, and so forth—all the effort it takes to produces a strong piece of writing.

Even after roughing out that approach, however, I made dramatic revisions. One was to seek out and add quotes by woodpecker experts. Another was to axe my introduction. At first, I had recounted my experience with Acorn Woodpeckers. That intro was okay, but I decided that it didn’t really add to the book, so out it went! What might be readers’ favorite feature of the book, the “Photo Bloopers” spread, was a last-minute addition. I was lamenting our failure at getting really great Arizona Woodpecker photos and just decided, “Well, what if I just put these imperfect photos in and call attention to the fact that we tried—and failed—at photographing these uncooperative critters?” That turned out to be a terrific revision. Besides the above points, I went through countless rounds of tightening, recasting, replacing verbs, and so forth—all the effort it takes to produces a strong piece of writing. AAAS/Subaru/Science Books & Films Prize for Excellence in Science Books.

AAAS/Subaru/Science Books & Films Prize for Excellence in Science Books.

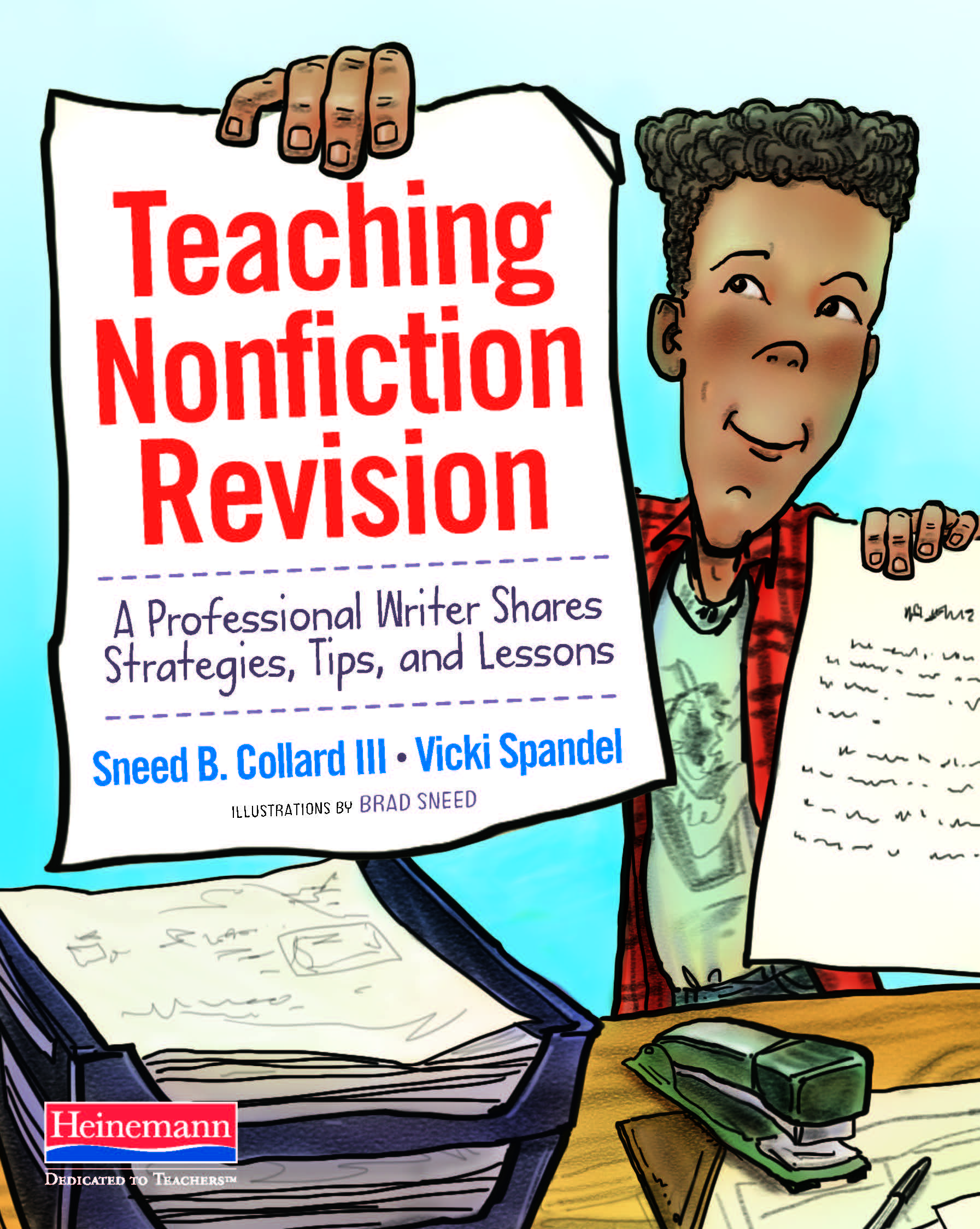

m specially designed to make the teaching of revision streamlined and easy. No matter what genre you teach, Teaching Nonfiction Revision will guide you and your students right through the revision process. You’ll have a good time, and get better at teaching revision than you ever dreamed possible. Lessons are posted online so you can print out and distribute just what you need when you need it. Bonus: I’m Sneed’s co-author, making sure he doesn’t wander off-topic to write about birding in Montana.

m specially designed to make the teaching of revision streamlined and easy. No matter what genre you teach, Teaching Nonfiction Revision will guide you and your students right through the revision process. You’ll have a good time, and get better at teaching revision than you ever dreamed possible. Lessons are posted online so you can print out and distribute just what you need when you need it. Bonus: I’m Sneed’s co-author, making sure he doesn’t wander off-topic to write about birding in Montana.