Miss Moore Thought Otherwise: How Anne Carroll Moore Created Libraries for Children. 2013. Jan Pinborough. Illustrator: Debby Atwell. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 40 pp.

Miss Moore Thought Otherwise: How Anne Carroll Moore Created Libraries for Children. 2013. Jan Pinborough. Illustrator: Debby Atwell. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 40 pp.

Genre: Informational narrative/biography/history

Ages: Grades K and up.

Summary

From the time my son was an infant until well into elementary school, we used to visit our local library at least three times a month to check out a fresh bagful of books. So, first of all, after reading this book, I need to say, “Many, many thanks to Minerva Sanders, Lutie Stearns, Mary Wright Plummer, Caroline M. Hewins, Clara Hunt, and Anne Carroll Moore!” (There are most likely many others to thank whose names are not listed here. The National Women’s History Project website reminds us, “Even when recognized in their own times, women are frequently left out of the history books.”) This formidable group of women librarians helped change attitudes about children and reading, and paved the way for the development of children’s libraries. Anne Carroll Moore, as readers will learn in Jan Pinborough’s informative picture book, Miss Moore Thought Otherwise, used the force of her tenacious personality and her position at the New York Public Library to promote and expand the concept of children’s library services both here in the United States and in many countries around the world. (Be sure to read the “More About Miss Moore” section at the end of the book.)

It may be hard for us to believe now, but in Limerick, Maine in 1880, when Miss Moore was nine years old, attitudes about children and reading were very different from the way we think today. Kids weren’t allowed in libraries and books for children, if there were many, were often kept locked up. Children couldn’t even put their hands on books, much less check them out and take them home. But when it came to libraries, children’s books, and reading for both boys and girls, thankfully, “Miss Moore thought otherwise.” She moved to New York to attend the Pratt Institute library school. Her first job was at the Pratt Free Library working in the new children’s room, where kids could actually take the books off the shelf! Her “otherwise” thinking at the Pratt led her to the New York Public Library system. It was here that Miss Moore’s vision for children’s libraries really came to life. Her faith in children helped her persuade New York librarians to allow kids to borrow books, take them home, and be trusted to return them. My son’s bag of books might never have happened without Anne Carroll Moore. Thank you, Anne, for always thinking “otherwise.” And thank you to Jan Pinborough and Debby Atwell for bringing Anne’s story to light. It’s up to us now to help get Miss Moore Thought Otherwise onto library shelves, into classrooms, and into the hands of young readers.

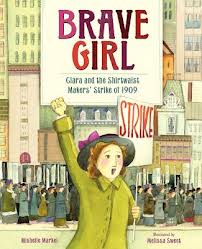

Brave Girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Maker’s Strike of 1909. 2013. Michelle Markel. Illustrator: Melissa Sweet. New York, NY: Balzer + Bray. 32 pp.

Brave Girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Maker’s Strike of 1909. 2013. Michelle Markel. Illustrator: Melissa Sweet. New York, NY: Balzer + Bray. 32 pp.

Genre: Informational narrative/biography/history

Ages: Grades K and up.

Summary

Clara Lemlich, like Anne Carroll Moore, was also a young woman who thought and acted otherwise, and even became the leader in an otherwise movement that led to big changes for women and workers in the early 1900’s. In Michelle Markel’s inspiring new picture book, Brave Girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Maker’s Strike of 1909, readers are introduced to a real fighter, young Clara Lemlich. Clara and her family immigrated to New York from the Ukraine to escape government persecution and find a better life. Barely speaking any English, Clara wants to go to school but is forced to seek work when her father is unable to find a job. Fortunately for her family, Clara does find work, but unfortunately for her and thousands of other young immigrant women, the work is in the garment industry. But as the author reveals to us, Clara has “grit,” and she “knows in her bones what is right and what is wrong.” Clara takes the work and faces it head on. The pay is barely enough to pay for food and rent and the working conditions are inhumane. Author Markel’s text and illustrator Sweet’s drawings and layout work seamlessly to present to young readers the harsh realities of the factories without being too scary. The pages showing an overhead view of the rows of workers crammed together, drops of blood on fabric, and a padlocked door are great examples of visuals and clear, direct text working together to help readers. On top of her hard work and long hours, Clara pushes herself by going to school at night. She just won’t quit! And she won’t accept the idea that she and her fellow workers have to be treated so poorly. Clara begins to talk with other workers, men and women, about organizing a union and striking to get better working conditions and pay. When she convinces her coworkers to walk out or picket, she and the others are fired, arrested, and even beaten. But she is “uncrushable,” and her spirit is “shatterproof.” Clara knew that her cause needed something bigger—a gigantic strike of garment workers at hundreds of factories! In 1909, Clara helped to lead the “Uprising of 20,000” garment worker’s strike. It didn’t happen overnight and it wasn’t easy, but Clara’s leadership, her grit, her uncrushable determination, and shatterproof spirit led to higher salaries, shortened workweeks, and safer factory conditions for workers in New York and across the country.

(These books will make a terrific twosome if used in tandem in your classroom. Clara and Anne’s lives, drives, and personalities have a great deal in common, so I’ll outline some ideas for their use as a duo, along with suggestions for their use as stand-alones.)

In the Classroom

1. Reading. As always, you’ll want to preview each book prior to sharing with students. I like to read picture books two to three times—I don’t want to miss anything! The illustrations in each deserve sharing as well. Miss Moore’s colorful folk-art scenes reflect both her small town background and her life in big-city America at the turn of the century. Brave Girl’s blend of watercolors with images of ledgers, paychecks, dress patterns, and close-ups of bits of fabrics stitched across the page help to bring Clara’s factory world and the working world of immigrants to life. Using a document camera will help students absorb the images and make clearer connections to the texts.

2. Background. Each of these books provides enough historical background and context to ease students into the lives of these historical figures. It might be helpful to locate New York City on a map and then find out what your students may know about the city—Big Apple, Yankees, Knicks, Broadway, Statue of Liberty, etc. Why was New York such a magnet for so many people near the turn of the century?

3. Personal connection. Miss Moore Thought Otherwise—With this book, encourage students to talk about their library experiences, both at school and at public libraries. What do they like to do at the library? How many of your students have a library card for their local public library? (At the Beaverton City Library, there is no minimum age for a card—kids can get a card whenever parents/guardians decide they are ready.) Have them imagine what it would be like if they couldn’t check out or even touch the books. What if only their parents could go inside? How would they feel if there were only books for boys/girls?

Brave Girl—The factory where Clara worked made women’s clothing, and the majority of the workers were young women themselves, some as young as six. What do your students know about how and where their own clothing is made? Have any of them ever had a “job?” What have they done to earn money for themselves? One of the issues Clara fought against were the “rules” of her workplace—how much she was paid, what would happen if she were late to work or bled on the material, the amount of time for her lunch break, etc. Have your students discuss the rules of their worlds—home, school, classroom, or playground. Are there any rules they believe are unfair? Have they ever worked to change a rule at home or school? Have you or any of your students ever stood up for something of personal importance?

4. Topic/Message. Each of these books is a biography, where readers are given a behind the scenes look into the life of a person who may be new to them. Beyond when they were born and where they lived, what do your students believe the authors really want readers to remember about these two women? Why do you and your students think the authors picked Anne Carroll Moore and Clara Lemlich to write about?

5. Persuasive writing. Both Clara and Anne worked to change the beliefs and attitudes of people who disagreed with them to make their worlds better places for themselves and others. How did each of them do it? Think back to the discussion of the rules that govern their worlds of home and school. Have students select a rule they would like to change, describe their positions, and then plan how they would make their cases and persuade those in charge. (It might help to have them think, “What would Anne/Clara do? to convince someone on the other side of their argument.) It would be both fun and useful with younger students to do a little acting/role playing with each side of their issues. In persuasive writing, it’s important to understand both sides of the argument and anticipate counter arguments.

6. Genre. The Common Core Standards divide writing into three broad genres: narrative, informational writing, and argument. Into which category do authors Markel and Pinborough’s books seem to belong? Biographies, if done well, are probably a blend of all three. They are informational—providing facts and a sense of a timeline—but also tell the story (narrative) of a person’s life, giving readers a way to connect as they try to persuade us about the importance of the subject’s accomplishments or contributions—thankfully. Without the narrative elements, these books could end up being a list of dry facts. Have your students try writing/talking about Anne or Clara as if their lives were a story—Once upon a time there was brave young girl who came to America with her family…See how much information they are able to remember and include.

7. Informational writing. The causes that Anne Carroll Moore and Clara Lemlich made the focus of their lives remain in the headlines today. In many cities today, public libraries have been closed or have limited hours/services due to funding problems. And many schools (including where I live) have made the tough choices to cut back on librarians and library services in the face of severe budget reductions. Working conditions and fair/equal pay continue to be issues for workers in the United States and around the world. Invite students to choose one topic for further exploration, either as a class, small groups, or individually, depending on age. Ask them to research and write about their selected topics or create a short play/speech/public service announcement to help bring the issue to life. The bibliography of Brave Girl is divided between general and primary sources. This distinction may be one you wish to explore with your students. What is the difference? Are there certain topics/genres where primary sources are essential? Have them find bibliographies in other books. How many sources were used? What kinds of sources—the Internet, books, interviews, film, etc.—were used? Why is it always important to use more than one source and kind of research in informational writing?

9. Comparison/Contrast. Used together, these two books make ideal choices for introducing or expanding the concept of comparing and contrasting. Have students help you create a T-chart for a closer look at Anne and Clara in terms of their backgrounds, education, family, etc. As you discuss your chart, help students look closely for similarities and discern differences. You could even help your students create sentences/structures that help them express their findings, especially if the sentence structures involve elements (conjunctions, internal punctuation, etc.) that are new to them:

Examples

Both Clara and Anne lived in New York City.

Although each of the young women worked for their causes, Clara often faced physical danger and arrest.

10. Reviews. Anne Carroll Moore was determined to stock libraries with not just books for kids, but great books for young readers. She created lists of recommended books for libraries and wrote reviews of books in newspapers and journals to make sure that quality books were being published. Anne also invited authors and illustrators to visit her libraries to meet face to face with their readers. Your students could create their own lists of recommended books, do book talks about their favorites, and even role-play and answer questions as a favorite author. Share some book reviews with your students as models for their own reviews of new (or new to them) books.

11. Voice/Dialogue/Sentence Fluency. The Common Core Standards aren’t as clear about the writing trait of voice as I would be in my own classroom. Where they do emphasize some important components of voice—writers choosing an appropriate style in consideration of both audience and purpose—I think they neglect the developmental nature of the concept of voice. Younger writers need help understanding that voice comes from a focused idea, being an “expert” on your topic, making sure your thoughts make sense and are organized, choosing words that paint pictures for readers, building sentences that flow, and knowing your audience. It’s a nurturing process that involves all the traits and lots of strong models, like the two books being discussed here, and goes all the way back to number one on this list—reading the book aloud. I think it would be fun with these two books to “hear” the voices of their subjects, Anne and Clara. What if these two historical figures met? What would they talk about? What would each person’s voice sound like? If you created the T-chart suggested in number nine, you could use it to help students write some conversational dialogue. What can you and your students do to make sure each young woman has her own voice? Does their conversation sound like real people speaking? These could be read aloud, recorded like a radio interview, or even filmed.

Anne Carroll Moore Clara Lemlich

12. Word Choice. Work with your students to develop lists of key/important words used by each author as they describe their subjects or tell each person’s story. Discuss what it means to think “otherwise,” a phrase used not only in the title, but also at important moments for Anne throughout the book. What does author Markel mean when she says that Clara has “grit” or is “uncrushable?” Pay close attention to the verbs each author chooses. For example, here are a few of the verbs chosen by author Jan Pinborough as she tells Miss Moore’s story—trusted, created, persuaded, pushed, pulled, wrote, encouraged. What do these choices tell us about Miss Moore? Look carefully at these choices from Brave Girl—locked, bend, hurry, hiss, crammed, bleed, fired. What does the author want us to know about Clara’s working life?

13. For additional information. The authors each provide a More About… section focusing on their subjects, time periods, and issues, along with a bibliography for further research. For older students looking for a connection to Brave Girl, check out the November 30, 2011 post about Albert Marrin’s book, Flesh & Blood So Cheap: the Triangle Fire and Its Legacy. The National Women’s History Project site, nwhp.org, is another good resource for more information about Women’s History Month. And to discover more about the authors and illustrators:

Miss Moore Thought Otherwise—

janpinborough.com

debbyatwell.com

Brave Girl—

michellemarkel.com

melissasweet.net

Coming up on Gurus . . .

Next up, Vicki reviews Wonder, by R.J. Palacio, a 2013 Newbery contender with an important message about kindness. Thanks for visiting. Come often—and bring friends. Remember, for the BEST workshops blending traits, common core, workshop, and writing process, call us at 503-379-3034. Give every child a voice.

Vicky and Jeff,

A thoroughly wonderful post. Thank you so much!

Thank you so much for your kind comments, Michelle! We hope you’ll visit us often.

Michelle,

You are most welcome! As you know, it’s wonderful to hear feedback from readers. The bigger thanks go to you for your excellent book. Please visit us again and let us know about your next book.

Appreciatively,

Jeff and Vicki

Hi Vicky and Jeff,

Thank you for this wonderful and insightful post. I can’t wait to hear how teachers use these books in their classrooms.

Best wishes, Melissa

Melissa,

What an honor for us to hear from both the author and illustrator! Your comments are greatly appreciated, as is your wonderful artwork. Please, drop in anytime.

Take care,

Jeff and Vicki