Last Stop on Market Street. 2015. Written by Matt De La Peña, illustrated by Christian Robinson. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons. Unpaginated.

Genre: Picture book

Ages: Grades K-2 (and up)

Summary

CJ and his grandma have a routine they follow each Sunday after church—they ride the city bus all the way to the last stop on Market Street. On this particular Sunday, CJ’s not too thrilled about making the journey, and he doesn’t keep his lack of enthusiasm to himself. His unhappiness comes out in a string of questions for his grandma—Why do we have to wait for the bus in the rain? Why don’t we have a car? Why do we have to go to the same place every Sunday? Why don’t any of my friends have to go? Of course, there are many more questions, and none of them faze grandma or her sunny disposition in the least. She’s ready and knows just how to answer to help work CJ out of his funk. By the time they reach “the last stop on Market Street,” and walk to the shelter where they volunteer, CJ is looking at his world, urban warts and all, through a different lens and is more than glad that he made the trip.

In the Classroom

- Reading. As we always suggest, it’s best to read the book more than once to yourself prior to sharing it with students. I also like to read a book like this out loud, so I can hear how it sounds as I voice each character. It’s good to remind myself that I’m modeling expressive reading for my students. When a book is as well written as this one, it’s easy to find and stay in step with the natural rhythm of the words. I’ll mention it again later, but the active verbs energizing each sentence help make it even easier to read. If verbs are the engine of every sentence, then Matt de la Peña is a first-class writing mechanic. His verb choice has each sentence running smoothly, from the opener to the wrap-up.

You’ll want to use a document camera to help students zoom in on Christian Robinson’s vibrant illustrations—a blend of paper cutouts and paint—to help young readers see and feel each part of CJ’s journey. I particularly like the way he makes each passenger on the bus an individual character—and not just background—with the inclusion of one or two distinct details.

- Background. The world of CJ and his Nana is urban—neighborhoods with trees, brownstone houses/apartments, sidewalk vendors, city-buses, city-traffic, graffiti tags, and abandoned buildings. Their bus trip clearly takes them from their familiar residential neighborhood surrounding their church through the city to a part of town where CJ feels the need to hold Nana’s hand. Again, she’s not fazed at all by the change in scenery. She’s smiling all the way to their destination—a soup kitchen where she and CJ help serve the needy patrons. If your students live in a more suburban, small town, or rural environment, much of the bus ride from church to the end of Market Street will need to be discussed/previewed and compared to where they live. Sharing suggestion: Using a document camera/projected images from your computer, share and discuss some images of city life—busy streets, tall buildings, public transportation—buses, light rail, etc., to help students connect to CJ’s world.Discuss with students how they get to school and around town. Many of your students may ride buses to school, but they may not have experienced public transportation like CJ and Nana. You may also want/need to familiarize students with some information about soup kitchens/shelters that provide meals and services to people in need. Some of your students may have participated in clothing/food drives or helped to feed the hungry. This may be a sensitive/personal topic for some of your students whose families are in need. You know your students best.

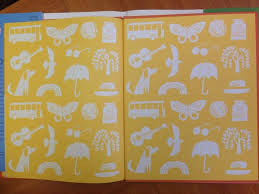

- Organization/Word Choice.It’s easy to overlook the endpapers of books. As a reader, the excitement of getting into the story and illustrations can make it easy to flip right past the inside covering, flip over the title page, and jump right into the reason you grabbed the book in the first place. While it’s true that many books may use a plain colored paper, this book has used white images (on a golden yellow background) of 12 items clipped from the book’s illustrations, repeated like a wallpaper pattern. Take a picture (or photocopy) of the end paper. Depending on your class size, you may only need one or two copies. Cut out the images and distribute one—make sure that there will be more than one student holding the same image. Ask each student, one at a time, to hold up and name/describe the object in their image—e.g., umbrella, bird flying, guitar, etc.—to make sure they know what they’re holding. As you read the story, ask students to look closely to find their image as you show each page of illustrations. When they see their image, hold it up and, when invited, bring it up to the front white board or chart paper. On one section of the board/chart paper, attach one of the images. With the students’ help, name it and write its name underneath. This group of labeled images will become a collection of words for students to use (like a word wall) in their own writing. Attach the other copy of the same image to the board/chart paper to create an organizational timeline, sequencing each image from beginning to end. When you have used all the images, see if any students think they tell the story using the timeline as a reminder.

You could also use the process of naming the images as a way to make predictions in advance of reading—What is the setting? Ideas about characters? How are the images connected? What do you think will happen?

- Central Topic/Theme/Message.What is the central message of the book? Why do you think author Matt de la Peña felt it was important to tell CJ and his grandma’s story? (Be sure to point out that both the author and illustrator mention grandmothers on the dedication page. Don’t forget to share the author and illustrator’s bios. Christian Robinson mentions that he “grew up riding the bus with his nana—just like CJ.”)

- Details. Use the image timeline your students created to emphasize that they represent key details in the story—if the author had omitted any of them the purpose, direction, and outcome of the story is affected. Leaving out some of them—the bus, guitar, dog, etc., makes it impossible to tell the story. Ask your students to retell the story without the bus ride. Talk about all the big and little changes to the story.Character details—I mentioned earlier that the illustrator, Christian Robinson, is able to create clear individuals—CJ, Nana, bus passengers, people at the shelter—by including one or two distinctive details for each character. Show your students the illustrations of the bus passengers (or the shelter patrons). Have them name each passenger’s distinguishing details—clothing items/colors, hair, accessories, etc., while you record their ideas. I think they might even have fun giving each person a name. You could even take it one step beyond and have them create back-stories for them or ideas about each passenger’s plan for the day/destination.

- Character details—I mentioned earlier that the illustrator, Christian Robinson, is able to create clear individuals—CJ, Nana, bus passengers, people at the shelter—by including one or two distinctive details for each character. Show your students the illustrations of the bus passengers (or the shelter patrons). Have them name each passenger’s distinguishing details—clothing items/colors, hair, accessories, etc., while you record their ideas. I think they might even have fun giving each person a name. You could even take it one step beyond and have them create back-stories for them or ideas about each passenger’s plan for the day/destination.

- Reading for meaning.At one point in the book, the narrator says, “The outside air smelled like freedom, but it also smelled like rain…” What does he mean by this? What if he had said that the air smelled like danger…? the air smelled like Monday? the air smelled like Saturday morning? (Note:Young students may struggle a bit with this, but many will enjoy the challenge of a discussion with philosophical depth. They may surprise you—as I’m sure you’re surprised every day—with their understanding.) This discussion also opens the door to the use, meaning, and purpose of similes in writing and speaking. This kind of comparison, I believe comes naturally to students, especially in conversation. I think it’s important to help students recognize figurative language, name it, look and listen for examples during reading and speaking, and then use it with purpose in their own writing.

- Word choice–Verbs. Earlier, I suggested that verbs are the engine of every sentence. Matt de la Peña expresses direct, visible action with every verb choice. As CJ left church in the book’s first sentence, he “…pushed through the church doors, skipped down the steps.” On the second page, the rain “…freckled CJ’s shirt and dripped down his nose.” Strong choices like these need to highlighted for student writers and readers. I like to have young students physically act out verbs—to really feel the action or draw pictures of the verbs acting on the objects. What if CJ “went through the church doors,” or the rain “got on CJ’s shirt.”? What happens when students try to act out or draw these actions? What happens to readers’ involvement in the story when verbs are flat and passive? What happens to the writer’s big idea?

- Writing opportunities.Ideas for writing jumped out at me from every page of this book. I’m going to list several suggestions but leave it up to you to shape them to the interests and needs of your students. Depending on the ages of your students, these suggestions could be done as individual or group writing.

- CJ and his Nana have their Sunday routine. Discuss the concept of routine with your students. What routines do they follow (besides going to school)? What is their Saturday/Sunday/weekend routine?

- What experience do your students have with public transportation—buses, subway, light rail, etc.? Describe a person you have seen while riding public transportation. Does your city have public transportation? Research the different modes of transportation a city/town might have. In your opinion, are CJ and his Nana smart to not own a car?

- Compare (through experience or research) the differences in city/urban living with life in a smaller town or rural area. After researching this topic, write an opinion piece arguing for/against city versus country/small town living.

- Research the training of service/guide dogs. Which breeds of dogs are easiest to train for these purposes? What kinds of services are these dogs trained to perform?

- Write about an experience with a grandparent or older relative/close friend. What can you learn from senior citizens?

- Write about an experience when you volunteered to help a friend, family member, or neighbor. Have you ever helped out, like CJ, at a church or shelter?

- Poetry—Read Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem called “Rain.”

The rain is raining all around,

It falls on field and tree,

It rains on the umbrellas here,

And on the ships at sea.

Write a poem or personal experience story about being out in the rain. What’s fun about the rain? What’s not so fun about rain?

- Closing his eyes and listening to the man play his guitar helps CJ change his mood. What do you do to put yourself in a brighter mood?

- What kind of music do you listen to? Try to describe/explain why you like listening or playing music. How do different kinds of music make you feel? If possible, collaborate with your music teacher for some help with this. Listening and moving to different types of music is a natural way to help conceptualize voice (human presence, sense of the individual in writing) for younger students.

- CJ’s Nana tells him, “Sometimes when you’re surrounded by dirt…you’re a better witness to what’s beautiful.” What do you think she is trying to tell him? What do you think is “beautiful” in your life?

- Conventions–dialogue. In number 6 above, I suggested having students name and create back-stories for the bus passengers or shelter patrons. Asking students to create dialogue between these newly-brought-to-life characters, is a great way to introduce and practice the conventions writers use when their characters converse. Rather than just tell your students about using quotation marks and commas, I suggest using your document camera to zoom in on a few examples of dialogue from the book. What do your students notice when CJ or his Nana are talking? What happens to your voice when you read the parts inside the quotations? What might happen to readers if writers forget to give them the appropriate clues/cues?

- More titles. Here are a few (and just a few) more titles of books you and your students might want to explore, especially if you and your students do not live in an urban area. (You probable have several titles you could add to these examples.)

One Monday Morning. 1967. Written and illustrated by Uri Shulevitz. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

Something Beautiful. 1998. Written by Sharon Dennis Wyeth and illustrated by Chris K. Soentpiet. New York: Doubleday.

The Snowy Day. 1962. Written and illustrated by Ezra Jack Keats. New York: Penguin. Winner of the Caldecott Medal-1963.

The Gardener. 1997. Written by Sarah Stewart and illustrated by David Small. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

For more on the picture books and YA novels from author, Matt de la Peña, visit:

For more about the wonderful art of illustrator, Christian Robinson, visit:

Coming up on Gurus . . .

Next up–some reflections on and reactions to Thomas Newkirk’s extremely thought provoking, Minds Made for Stories: How We Really Read and Write Informational and Persuasive Texts. Every page makes me think! Thank you for stopping by, and as always, we hope you will come often and bring friends. Please remember . . . to book your own writing workshop featuring the 6 traits, Common Core Standards and the latest and greatest in young people’s literature, give us a call: 503-579-3034. Meantime . . . Give every child a voice.

I am looking for a children book series with multi-cultural characters. Do you know of any? This is for a first grade class. Thanks