by Vicki Spandel

Introduction

For most of my life, I’ve written educational materials and journalistic stories. Then one day I took a break to look out my office window and there, staring up at me, was the most beautiful cat I’d ever seen. Incredibly heavy long-haired coat, green eyes, and a stare that wouldn’t let you go.

Where had he (or she) come from? This was winter, a time when most people who live in my mountainous part of Oregon head to Arizona as fast as their four-wheel drive vehicles can take them. Had someone left this gorgeous creature behind? Before I could get close, the cat vanished as if never there, leaving nothing behind but the image in my head. There had to be a story here. On a whim, I sat down at my keyboard and began writing the tale of a cat with an irresistible urge to explore.

At first, my story writing adventure was mostly for kicks, a kind of writing therapy, but I had so much fun inventing that I couldn’t stop. Before I knew what was happening (and with significant encouragement from a friend—more on this later), I had a book titled No Ordinary Cat.

My little story (which I originally thought would run about five pages) evolved into a children’s chapter book, primarily aimed at young readers, though I’m hoping it will gain fans among adults who love cats as much as I do. It also grew to twenty chapters.

Of course, books aren’t finished when you write the last line. They take revision—a lot of it. In fact, I worked on this little book off and on for nearly two years. And during that time, I learned that if you don’t love revision—and I mean truly love it, all the messiness of adding and chopping and reworking repeatedly—you shouldn’t even think about writing a book. I do love it, though, and this book became my passion. So much so that I’m thinking of doing a sequel.

As I worked on my cat book, I learned other things too, some of which echo writing wisdom that applies to any writing. Storytelling, however—as I would discover—has its own little nuances.

Here are some thoughts you may find helpful as a writer or teacher of writing.

My 9 Tips

Tip 1: Don’t lock in your message—let it “bubble up” as you write.

Ever see a movie that just doesn’t seem to go anywhere? Watching it is torture. The plot wanders aimlessly, and all you can think is, Will this ever end?

I certainly didn’t want anyone feeling like that about my book. I could avoid this, I thought, by having a clear main idea, a message, a point to make. I was sort of right. The part I didn’t get right was feeling I had to pinpoint my main idea with laser precision before I’d even typed my lead. What I learned as I wrote was that my message was redefining itself with every added chapter and character and new situation. This, I learned, is part of the joy of writing fiction. And it is very different from writing a report, summary, how-to book, or any other nonfiction.

When I started this book, my core theme was that cats are essentially wild animals, even when domesticated, and guided by that wildness, are driven to explore despite any danger that poses for them. That’s still an integral part of the story, but it’s no longer the main theme.

The central idea in my final draft is that friendship has healing powers. It is not only life changing, it can be life saving. That’s a big leap, and it took quite a lot of revision (plus a whole raft of new characters) to get there.

Try this in a conference if you have a student whose writing (fiction or nonfiction) seems to meander. Ask them to define in one sentence what the main message of the piece is. If they can do that, revision will be far easier, and will truly make the writing better as opposed to just changing it for the sake of change.

Don’t forget, though, to also ask, Do you find your main idea or message changing as you write? Are you finding you have more to say than you thought—including things you didn’t anticipate? It may not occur to young writers that this can happen, given how hard we’ve hammered home that “Have a main idea” message. It hadn’t occurred to me, but once I got comfortable with it, stopped fighting it and allowed it to happen, I realized how much better writing can be when you let your message evolve, expand, and speak for itself.

Tip 2: Let your characters help you figure out the plot.

The hardest part of writing fiction, I’d always thought, was figuring out the plot. Did I lay it out in a flow chart titled “Plot”? List the main events? What??!!

The solution—now so obvious—just hadn’t come to me: namely, that in much the way our lives are extensions of ourselves, plot is an extension of a book’s characters. Think of Ahab fixated on that whale, Gatsby with his green light, Holden with the little kids, Winnie loving honey and Piglet, Charlotte loving Wilbur.

I started with a general idea—a cat who longed for adventure and set out to explore a wilderness he wasn’t prepared to survive. That’s a start, all right, but it’s hard to make a whole book out of it. My biggest problem? I couldn’t envision how the book would end. I needed that little cat to show me.

As my characters evolved, Rufus, the main character, showed himself to be driven, almost obsessed, by curiosity. Recognizing and respecting that, I let him follow his instincts in every situation. He would wish himself (wisely or not) away from home and out into a wilderness he knew nothing about, he would let himself be lured down a path that would inevitably lead to danger, he would make friends with strangers. What occurred as a result of these decisions on his part became my plot. But I never felt I was making the decisions for him. They came out of who he was—or who he was gradually becoming.

You’ll hear fiction writers say their characters “talk” to them. This is real. It happens. You don’t hear voices exactly. It’s not some Joan of Arc thing. It’s more like hearing friends talk in your head, advising you to hey, go ahead and take that trip, buy that house you know you love, stop working so hard, cut your hair, do more yoga.

Characters, as you develop them, become just as vivid and real as those friends who surf your mind waves. You can’t write dialogue that doesn’t sound like them or dump them into situations they simply would never be caught in. Try it and they object, loud and clear.

Getting to know your characters makes writing more fun and less predictable. You can ask them, Would you take a risk to get what you want? Would you risk your life? What do you care about most? What if you can’t get it? Who or what stands in your way? What are you going to do about that? Their answers lead to an ending that works because it feels right. It fits them, and it’s what might actually happen—with a few twists and turns of fate thrown in, of course.

Try putting your characters at the center of things, and let the plot swirl around their wishes, fears, hopes, and decisions—good or bad. If you’re surprised at how things shake out, you’re probably doing something right.

Tip 3: Do your research.

Research isn’t just for nonfiction reports or books. It’s for all writing.

You cannot write with confidence about anything you don’t know well, and this is just as true for fiction as nonfiction. For my book, I researched not only cats, both domestic and feral, but other creatures as well. For example, in one scene, a cat is being hunted by a golden eagle.

Golden eagles are revered by many Native Americans for their courage and hunting prowess. This much I knew—so I chose the golden for that very reason. They’re formidable, and if you happen to be one of the animals they hunt, they’re terrifying. That’s what I wanted, the thrill that only comes with that level of risk. I wanted to push my cat character to the absolute limit of what she could do—but I wasn’t ready to write the scene by any means.

I didn’t know for sure what golden eagles weighed, what they ate, where they built their nests, how fast they could fly, how strong they were, how much they could carry, or a hundred other things. The book doesn’t include all these details, naturally. It’s a story, not a report. But the point is, knowing is what matters. You cannot write a scene in which a golden eagle attacks another animal without knowing how that might play out, who would most likely win, and how or why. It won’t be authentic. Readers won’t trust it. And that trust is something you cannot afford to lose.

Even when students are writing stories about things they believe they know well—their pets, their home town, school, family, video games, a favorite sport—encourage them to do at least a little research. If they uncover even one bit of new information they can weave into the story, I can almost guarantee it will be stronger.

Tip 4: Read everything aloud—more than once.

You’ve undoubtedly heard this sage advice many times. But—do you actually do it when you write? Do your students? Reading aloud helps you know whether—

- Your writing simply fills space or seizes readers by the lapels

- Your dialogue sounds natural or stiff and forced

- Your text is easy to read without a lot of rehearsal

- Your words are likely to evoke images, memories, or strong emotional responses

- Sentences vary or create a monotonous rhythm that puts readers to sleep

- Your lead is so strong it might make someone buy your book

- Your ending is a big fat let-down—or enough to make readers wish for a sequel

I read at least a portion of my book aloud every day as I was working on it. When you read aloud, you can’t skip over sections. You can’t ignore the bumpy parts. You discover missing or repeated words, passages that simply add nothing, dialogue that sounds like a badly written Soap. Reading aloud keeps you honest. But I learned another trick, too.

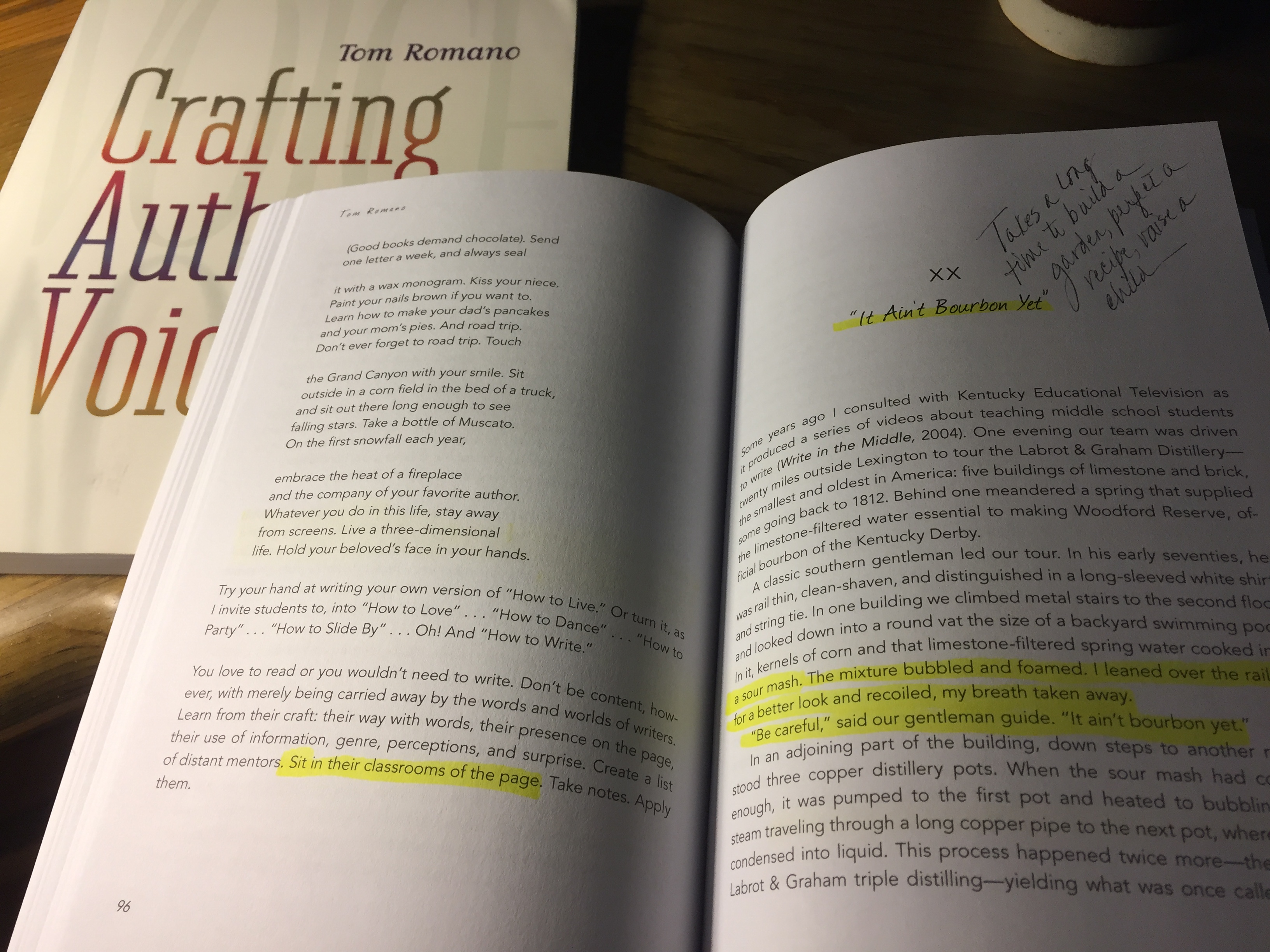

This may sound a bit strange, but it works. I “auditioned” various people to read aloud to me, and yes, I could hear their voices in my head—quite clearly, in fact. By the way, I got this idea from my colleague and co-author (Teaching Nonfiction Revision) Sneed Collard, who nearly always works with a writing group. Group members take turns reading one another’s work aloud so the writer can listen to his or her words in someone else’s voice. I’d love to hear my writing in just that way, but unfortunately, I don’t have a writing group right now, so I had to improvise.

At first, I imagined two friends read alternating chapters: Jeff Hicks (former Gurus co-author) and Darle Fearl (one of the best writing teachers ever). I’ve heard them both read aloud numerous times. They read with expression, and know how to hold an audience’s attention. They can switch on a dime from light and humorous to somber or melancholy. They know how to pause occasionally, creating a silence as powerful as any words. Over time, I discovered which chapters fit Jeff or Darle best, so I always had the voice I wanted for every scene, and their “readings” influenced my revision enormously, particularly with respect to voice, sentence rhythm, and dialogue. Ultimately, though, I wanted to hear the whole thing in a single voice other than my own.

I had some famous voices in mind—Meryl Streep, Susan Sarandon, Tommy Lee Jones, Peter Coyote, Sean Connery, and Tom Hanks. These are distinctive voices, but I mainly chose them because they’re voices I’ve heard countless times, so I figured conjuring them up in my head might not be too difficult—and I was right.

In order to make a choice, I “listened” to their voices on the first two paragraphs, and probably would have kept this imaginary try-out going for a while just because it was so much fun, but when I got to Tom Hanks, I knew I couldn’t do better. Tom can be tender and loving, serious, aggressive, bewildered, overwhelmed, mischievous, humble, sarcastic, comedic—or whatever the situation calls for. He has, in short, just the kind of flexibility good oral readers need. And because I’ve seen and heard him in many films, I had no trouble imagining how it might sound if he read No Ordinary Cat aloud.

Reality check: As you might suspect, I could not afford to hire Tom Hanks to actually create an audio version of my book. If only! But imagining how this might sound was not only entertaining, it was helpful in revising, especially when it came to dialogue.

I have to think that kids would also have fun doing this—choosing a voice to “read” their work aloud, if only in their imaginations. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying this can take the place of doing your own reading and having someone from a writing group read your work aloud to you. Not at all. Students need to do both those things. But I am saying that it’s an enjoyable alternative and one that adds a new dimension to how you hear your own work. Consider how much fun students might have discussing which voice they had chosen and why.

Tip 5: Leave it alone (for more than a day).

Every time I felt I was “finished” revising (and I was always happy with what I’d written), I’d leave the manuscript for a few days, then return to find a hundred things that cried out for change. How had I missed them?

This isn’t unusual. It happens, I think, to anyone who works on a single document for an extended period. You just can’t get to what you really want to say with one round of revision, any more than a sculptor can transform marble into a work of art with one stroke of the chisel.

A book lives in your head the whole time you work on it, and my husband quickly figured out that when I was staring out the window, I was “writing.” Thoughts and words and phrases cycled through my head endlessly. Nevertheless, I needed that time away from the keyboard to process things so I could make better choices when I dove in again. Writing doesn’t happen quickly. Nor should it.

One reason revision is so difficult to teach in school is that we just don’t have the time required. It’s impossible to write well without revising—more than once. But how is that supposed to work in the real world? Students have deadlines. Teachers want to see their students’ work on a regular basis so they can track progress and head off problems. They also want students to write on multiple subjects. All of this is understandable, and all of it gets in the way of making time for revision.

It’s unfortunate that students never know how satisfying it is to stick with a piece of writing for a while, to return to it, reflect on it, and revise it many times until it turns into something you love. It’s not just the piece of writing that changes when this happens. It’s the writer. Not only do you discover more ways to revise and more little things you can do to bring out meaning, but you simply get faster, more flexible and adept, more daring—and more capable of solving writing problems. And solving problems is really what revision’s about.

Any piece of writing can improve markedly if the writer leaves a draft for two, three, or even more days before returning to revise with new eyes. Let students do this regularly. But consider trying this, too: Have students identify one piece to work on periodically through the course of a semester or even a whole year. Those who take time to do this will be amazed by how much the writing changes and by how much more in control they feel as revisers.

Tip 6: Create a special, separate file for problem passages.

Sometimes it’s really hard to know exactly how you want to say something. You revise—maybe removing some words and adding others—then revise again. Problem is, now you no longer have your original to look at. And in spite of all your brilliant changes, maybe that was the best version! Grrrrrrrrr!

In the computer age, it’s simple to revise, but because changes automatically disappear, often difficult to make comparisons. Here’s another handy trick I learned from my co-author Sneed Collard–one that was invaluable in writing this most recent book.

When I cannot quite make up my mind about a passage, I copy the whole thing to a new blank page, then write one or two new possible revisions right beneath it. I give this new file a name and save it. That way, I can wait a day or two, come back, analyze and compare all options with a clear head. Everything’s right there in front of me, nothing’s lost. Here’s one short example.

In an early chapter of No Ordinary Cat, the main character, Rufus, approaches a pair of newly nested geese, who resent his intrusion. Rufus, who’s lived in a house all his life, has no idea what geese even are, so cannot recognize the danger he’s in. Here are several introductions to this scene. Being able to look at them all together made it easier to choose the one I liked. See which version you like best:

Rufus smelled the geese, but the scent was new to him, so he was more intrigued than afraid. The geese also smelled Rufus, and the dreaded stench of cat—instantly identifiable—had them bracing for a fight.

Rufus smelled the geese, but the scent was new to him, so he was more intrigued than afraid. For the geese, there was no mistaking the dreaded stench of cat. They braced for a fight.

Rufus smelled the geese, but the scent was new to him, so he was more intrigued than afraid. As he crept closer, the geese found themselves awash in the dreaded stench of cat—and they braced for a fight.

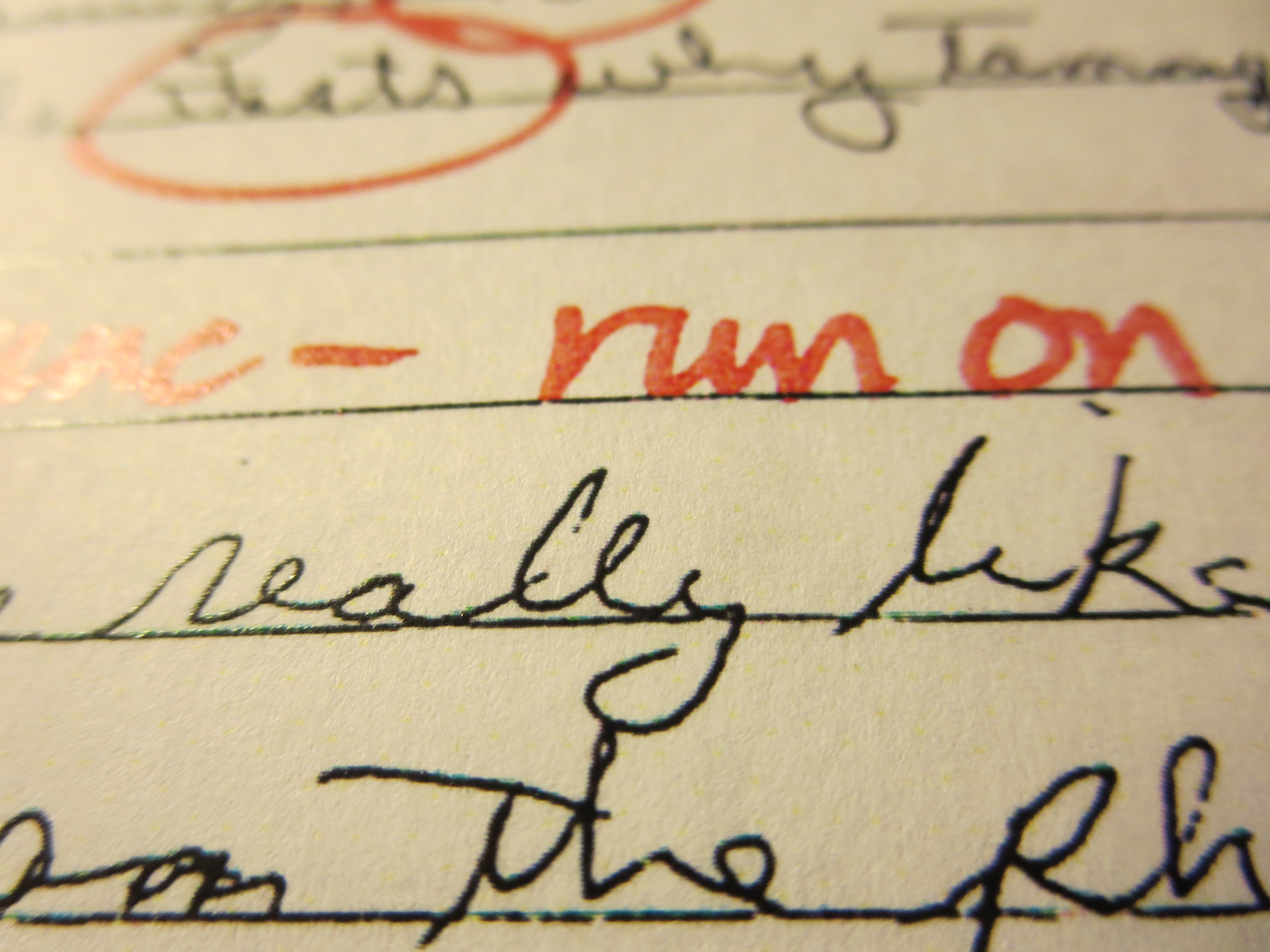

Tip 7: Remember that little things, like repetition, make a big difference.

Do you have some favorite words? Yes, you do—even if you’re unaware of it. We all do. I just love the word just, and it just slips into my writing way too often. This habit is just a whole lot harder to break than you might think.

When you write something two or three pages long, it’s relatively simple to avoid repetition because repeated words are so easy to spot. But what happens when you write a book?

It’s all but impossible to recall every repetition once you’ve written more than, say, ten pages. Wait a minute, though. Is repetition in a long document really such a big problem? Maybe the reader won’t even notice.

Maybe not. A little word like just might slip by undetected. But strong verbs like launch, slink, or zoom tend to stick in readers’ minds. When they pop up too often, it’s as if the writer ran out of things to say or hadn’t even troubled to reread or revise. If the writer doesn’t care, why should the reader?

Luckily, word processing offers an invaluable aid called “Navigation” that allows you to check how many times a particular word, part of a word, or phrase appears in a document. I used this daily. Sometimes, I admit, I was shocked to see how often I had used a word like, say, leap. Some of those repetitions had to go.

Now leap is a word with numerous synonyms: bound, jump, dive, spring, hurdle, vault, surge, and so on. The thing is, you cannot just grab one of these handy dandy synonyms and write on. They seem to all mean the same thing, but they don’t. Not really.

A mouse, for example, can jump but cannot really bound. That would be an unusually large mouse with extraordinary legs. A wave can surge onto the shore, but not hurdle. An eagle dives all the time when hunting, but doesn’t bound or spring or vault—unless it’s caged and its legs are tethered. Word choice demands that you visualize what you’re writing, making sure that you say precisely what you mean—not kind of what you sort of mean. This is especially critical in fiction because stories require so much description, characterization, action, and sensory detail. By the way, you can’t always get by merely exchanging one word for another. Often, I would wind up rewriting a sentence so I didn’t need the repeated word or a synonym. Or I’d cut that sentence altogether.

Minimizing repetition takes more than just looking at individual words, though. You also need to look for patterns. I routinely looked through each paragraph to see if I’d started and ended sentences in a variety of ways.

Look down my recent paragraphs from the post you’re reading and you’ll see these beginnings–all different:

- Do you have . . .

- When you write . . .

- Maybe not . . .

- Luckily . . .

- Now leap is a word . . .

- A mouse, for example . . .

- Minimizing repetition . . .

You probably didn’t notice these differences as you were reading. But if all my paragraphs had started the same way, you would most definitely have noticed—and you might have thought, “What gives? Is she asleep?” Repetition is only one example in writing where something small can irritate readers.

Something I learned from writing many action scenes is that as writers, we all have favorite structures, just as we have favorite words. I tend to like participles—not consciously (“Ooh, here comes a participle!”). It’s just how my writing mind works:

- Watching the hawk’s every move, she shimmied up the tree.

To my ear, that’s better than this:

- She watched the hawk’s every move as she shimmied up the tree.

Admittedly, there’s not a lot of difference. But the second option makes the cat sound relaxed, as if taking her time, even though she’s supposedly shimmying. It also makes it sound as if this watching and shimmying is in the past. The first sentence makes the cat seem more alert—as she needs to be in this scene. It’s also happening right now, so the reader is thrust into the action. So far so good. The problem arises when I use too many participles together:

- Watching the hawk’s every move, she shimmed up the tree. Eyeing her prey, the hawk moved in.

Overdoing anything kills impact. So have students look for repeated structures. This activity also helps them become aware of the many ways sentences can begin. You can also have students choose one sentence to write in multiple ways. A sort of stretching activity for the mind.

And you, or your students, might list the first words of each paragraph within a page or two, asking, Are the beginnings different in both wording and structure? If not, you’ve got one small thing to revise that will have an enormous effect on voice and fluency. Speaking of which . . .

Tip 8: Trust the 6 traits.

People have often asked me, Do YOU use the 6 traits when you write or revise? Well, wouldn’t it be odd if I didn’t? But here’s the thing: Everyone does. You can’t help it because the traits are nothing more than the qualities that make writing work—clear ideas, easy-to-follow yet occasionally surprising organization, voice, and more.

However, I probably don’t use them in the way you imagine.

I know of teachers who’ve had students memorize rubrics. That’s a total waste of time. I don’t know them by heart and I helped write them. I don’t keep a rubric by my elbow as I revise, either—nor should you.

The point of the traits is not—never has been—rubrics. The point of the traits is . . . concepts. Once students understand, really get, what it means to have clear ideas, compelling voice, word choice that stirs readers, or fluency that enhances the whole reading experience, they have no further need for rubrics. To be of any value, the traits need to reside in your head—expressed in your own words.

Moreover, I don’t consciously go through these traits one by one as I revise. How tedious would that be? But I do watch and listen for things like this as I revise:

- Am I boring or confusing my readers? Or showing them something they weren’t expecting? Are they still with me—or falling asleep? (Ideas)

- Do I have enough detail, the right detail—and no mind-crushing overload of sensory details? (Ideas)

- Did I start where the story begins? Or write two pages of gobbledygook before getting to the heart of the matter? (Organization)

- Am I rushing readers through this story? Trudging along? Moving at a good pace so something important happens in every scene? (Organization)

- Are readers asking, “How the heck did we get here?” or “Whatever happened to so-and-so?” or am I picking up loose ends and making needed connections? (Organization)

- Does the conclusion pack some punch? Is it too predictable? Did this story really end two pages ago? (Organization)

- Does the voice sound like me? Is it honest? And is it the voice I want? (Voice)

- Do my words ring true? Do they come as close to the image or impression or message in my head as I can possibly come? (Word choice)

- Is this easy to read aloud—and do I love the sound of it? (Sentence fluency)

I don’t have a checklist or chart of any kind because these concepts are just part of how I think as a writer. They’re probably part of your thinking, too. But again, you need to think of them in your own words, your own voice. That’s how you want things to work for students. A checklist is never part of you—and you want revision to be part of you.

Think of it this way. If you were picking out a car (or shoes or a dog or anything), you’d have certain things you’d look for, right? You know what they are. You don’t carry a rubric with you to the car dealership because—well, why would you? You don’t suddenly forget that style or technology or price or performance or color matter to you. The 6 traits are just like that. They’re all about what matters.

Tip 9: Remember—it’s never finished.

How do you know when you’re done revising? Good question! And the answer is more complicated than “It sounds good” or “My writing group likes it” or “I revised it once—and that’s enough!”

For me, the feeling is akin to trying on new shoes and finally finding ones that feel great. It’s a relief. I know these are the shoes that will make my feet happy. They look terrific, they feel comfortable, I’m not going to return them, and I’ll still like them next month when I take that long hike.

At the same time, there is no perfect shoe, and no perfect piece of writing. Every time I return to a piece of writing—any piece—I find something I’d like to change. Writers have, I think, a built-in editorial instinct that just operates this way. Heck, I revise books I’m reading, too—in my head. I don’t write on them. But still. It’s just what writers do. They can’t help it.

While working on my book, I’d go through my manuscript twice a day, usually making more revisions on the second pass. Finally, one day, I found myself not changing much at all. I was shortening an occasional sentence, changing a word here or there—and then, often as not, changing it back. But really, if I’m being honest, these changes were not improvements. They were making the document different but not necessarily better. Not more dramatic, more readable, more compelling. Change for the sake of change is not revision. It’s tinkering. When revision devolves into tinkering, it is time to stop.

That doesn’t mean the document is “finished.” There’s always something. Always. But unless I want to spend my whole life working on one piece of writing (and I don’t), I need to move on. I rationalize it this way (and it’s a good way, I think):

Whatever lessons I learn from future readings I can apply to writing I do down the road.

Adopt this philosophy. Think ahead—to all that writing waiting to be done in your future. Have your students do the same. Meanwhile, to define a reasonable point at which to stop, pay attention to the kinds of revisions you are doing. As long as you are—

- Rethinking ideas,

- Building in a surprise,

- Including details you didn’t think of before,

- Making connections clear,

- Creating a new character,

- Revamping or adding dialogue,

- Hacking off parts you don’t need or like,

- Coming up with better words, phrases, or even whole paragraphs,

- Reordering sections,

- Writing a whole new beginning,

- Writing a whole new ending,

- Writing from a different perspective,

- Restructuring sentences,

- Changing the voice or tone, or

- Condensing . . .

You are doing significant and important revision. Keep on keeping on. But once you find yourself—

- Agonizing over individual words for too long,

- Rewriting sentences with no appreciable change in meaning, sound, tone, or rhythm,

- Tinkering endlessly with punctuation (Dash? Ellipses? Comma?),

- Or worst of all,

- Making changes you wind up reversing the very next day,

you are probably tweaking, not revising. Stop. Hit reset. Time to write something new.

Before I go, let me extend not only my thanks but a long and enthusiastic virtual round of applause to my writing coach, developmental editor, and publication coordinator, Steve Peha (author of the award-winning Be a Better Writer). Without Steve’s unwavering encouragement and expert advice, my book might have remained in neutral for years to come. And I would never have enjoyed the learning experience and great fun I’ve had reworking it. Thank you, Steve! (Hope you’re up for a sequel!)

Stay in touch for more details on No Ordinary Cat, tentatively scheduled for release in spring of 2020. I’ll preview it then in all its glory, with illustrations by the incredibly talented Jeni Kelleher. Meanwhile, thank you for stopping by—and Happy Fall.