I know that the Common Core State Standards, and the changes in standardized testing accompanying the standards, are hot topics (if not controversial ones) for students, teachers, parents, school districts and boards, state legislatures, and many other public education stakeholders. So, let’s take a break from that conversation/discussion/pot-stirring for a few moments. I’m not going to mention the CCSS again in this post. Don’t read anything diabolical or political into this! I’m just hoping to emphasize that the instructional wisdom we offer in our posts about strong reading/writing classrooms is not different from what we would be suggesting if there were no CCSS. (Oops—I slipped up. From this point on, there will be no specific mention of the CCSS.) A balance and variety of great literature—fiction and non-fiction to dive into both as readers and writers, a balance of narrative, poetry, informational, and argument writing, teachers modeling through their own writing, teaching writing process and the six traits of writing, students as assessors—of their own writing, the writing of classmates, and the writing of professionals, students as revisers/editors, etc. These have always been important elements of strong reading/writing classrooms, regardless of grade level. It just so happens that the CCSS (last mention—I promise) also values and emphasizes these elements—directly and indirectly. And STG is here to help you make the connections.

OK, the lure of gold is calling to me, just like it did for thousands of adventurous souls willing to risk life and limb to strike it rich in the Yukon way back in 1897. Up dogs, up! Mush! We’re heading north!

Call of the Klondike: A True Gold Rush Adventure. 2013. David Meissner and Kim Richardson. Holesdale, PA: Calkins Creek.

Genre: Non-fiction, informational

Grade Levels: 4th and up

Features: Historical timeline, detailed author’s note, bibliography, photo credits.

168 pages (including back matter)

Summary

This true adventure story sprung from a bag of old letters, telegrams, and newspaper clippings belonging to the book’s co-author, Kim Richardson. The contents of this bag, passed down through family members, were written and collected by a relative of Richardson’s, Stanley Pearce, who along with his friend and business partner, Marshall Bond were two of the early wave of Yukon gold stampeders heading north in 1897. The authenticity of this tale is a direct result of the amazing primary source treasure of Richardson’s bag and the first-hand research and experiences of lead author, David Meissner. (See Author’s Note, page 156.) Readers will feel the weight of the hundred pound loads carried on the backs of Pearce, Bond, and the crew they enlisted. Readers will shiver in the sub-zero temperatures of the Alaskan and Canadian north. Readers will ache with hunger and exhaustion as their food supplies dwindle. And readers will twitch with anticipation and gold fever—could this be the big bonanza?—with each flake of gold shining in their pans or small nugget uncovered after hours of shoveling and sluicing. So, were they among the few who really did “strike it rich?” Or were Pearce and Bond among the many whose fortune was merely surviving the adventure and making it back to tell their tale? Up readers, up! Mush! Read on!

In the Classroom

1. Preparing for Reading. As always, take time to preview and read the book prior to sharing or involving students in independent reading. I suggest first reading the Author’s Note (page 156) to set the stage for all that David Meissner went through before doing the actual writing of this book. Because of all the primary source material available, Meissner and Richardson had a great deal of editing and transcribing work to do with the letters, telegrams, diary entries, photographs, and newspaper articles, along with the creation of original material to connect all the parts of the story. If you plan to use this as a partial or complete read-aloud, the photographs and other visuals, so important to this book, need to be shared with students using a document camera. This is a must to help readers connect to the textual elements.

2. Background–Gold. What do your students know about gold? As an anticipatory set, have students do a little brainstorming focused on the questions, “What do you know about gold?” “What do know about the Klondike gold rush?” What is their knowledge of gold as an element, its uses for jewelry and beyond, why it’s valued, where it’s found, its properties, etc.? This could be followed by some quick online research to gather some highlights about this element. Humans have been obsessed with gold for thousands of years, have adorned themselves with it, have hoarded it, destroyed the environment searching for it, and have killed each other for it—so really, what’s up with gold? This will help set the stage for understanding “gold fever,” the term “gold rush,” and help explain why two educated men from established backgrounds would risk everything for a piece of the action in the Klondike.

3. A Reader’s Reflection. Take a moment before diving into the book to discuss with your students how they as readers know when writers are “experts” on their topics— how, as a reader, they can tell when writers know what they’re talking about. What happens to readers when they are in the hands of an expert? Are they able to tell when writers are faking it or stretching their limited knowledge too thin? What happens to readers when they don’t have confidence that the writer is an expert?

4. Author’s Note—Research/Becoming an Expert. As I suggested to you in #1 above, I would have students begin their experiences with this book on page 156—the Author’s Note. Mr. Meissner begins by saying, “I didn’t know much about gold before this project.” What a fantastic thing for students to hear from the book’s author! How can you write a book about something you don’t know much about? Research! Research! Research! Ask your students to find out exactly what the author did to become an expert on his chosen topic. Begin a list of the kinds of research Mr. Meissner did prior to writing.

A. Met with Mr. Richardson, the keeper of the bag of letters, articles, diaries, telegrams, etc.

B. Read the contents of the bag and began sorting, organizing, and asking questions.

C. Answered the question, “How could I write about the adventures and hardships of the Klondike gold rush while sitting in the comfort of my home in the lower forty-eight states?” His answer? Retrace the steps of Pearce and Bond as much as possible—experience what they experienced.

D. Interviews, conversations, reading, etc.

E. (and so on)

What advice can they take from Mr. Meissner to use in their own writing? What advice might apply when you are writing about a personal experience—something you that happened to you, where you are already an expert? What do readers get when writers are “experts?” When writers really do their research?

5. Organization—Yukon Prep/Making Lists. Why do people make lists? What kinds of lists do you and your students make most frequently? Even if their lists aren’t written, do they have mental checklists for getting ready for school, preparing for a sports team practice, or preparing for a writing assignment? One big reason for making lists is, of course, to plan and organize thoughts, materials, or tasks prior to beginning a project. Schools even provide a supply list prior to the beginning of a new year to make sure students will have what they need. Ask your students to imagine they are going to spend the night at a friend’s house or with a relative. Have them make a list of what they would take with them—a supply list, of sorts. They may only come up with a few items. (Some of your students may have experiences with overnight camping—they could make a supply list for a trip like this.)

Meet with a partner or in small groups to compare lists and discuss the reasons behind each item’s inclusion. (Be sure to create and share your own list—prepping for an overnight stay, a weekend trip, or even a vacation.) What kinds of things were most common? Why? Could some of these items be considered as “essential” for “survival?” What does it mean if something is “essential?” Ask students to do an online search for “the ten essentials of hiking/backpacking.” Discuss why these items are included on the list and a computer, for instance, is not.

Now, look at the list on page 15, “A Yukon Outfit,” reflecting the kinds of supplies Pearce and Bond would have gathered before departing for the Yukon. What general categories—food, tools, clothing, etc.—of items did they bring? What factors would have to be considered when creating a list for a trip like this? Working with your students, create a new list of the factors suggested. Some ideas might be length of stay, weather conditions, terrain, time of year, mode(s) of transportation, proximity to “civilization,” etc. Using “A Yukon Outfit” as a guide, students could work in research groups to create “A Sahara Desert Outfit,” “A Miami, Florida Outfit,” “A Tasmanian Outfit,” etc.

6. Communication—Then and Now. Stanley Pearce agreed to write about his adventures as a correspondent for a newspaper, The Denver Republican. What’s a newspaper? (I’m only partially kidding with this question.) What does it mean to be a correspondent? In 1897, how did people get their news, communicate, and keep in touch? How do people do the same today? Create a T-chart to compare and contrast methods of communication, 1897 (then) and 2014 (now). Some things to consider placing on the chart: newspaper, email, phone, telegraph/telegram, computers, etc.

People still write and send letters today, but are they as important to communication as they were in 1897? The letters that Pearce and Bond wrote to family members contained news of their daily activities, personal health/well being, and updates on their progress in the gold fields. These letters would have taken weeks, months or more to reach family members who were anxiously awaiting the news. Return letters from home also took months to be delivered to the Yukon and may have travelled by train, ship, horse, dog sled, and human carrier. These letters were almost as valuable as the gold the men were seeking. Have your students ever written or received a letter? Try having them keep a mini-journal (a personal blog on paper) for a day listing, describing, and commenting on their activities in the classroom, on the playground, in the cafeteria and hallways. Imagine they are writing to a parent or family member far away—someone they haven’t seen or spoken with for a long time. Specific details will be important to the recipients—names of friends, descriptions of weather, food eaten, how even small moments are spent. Using their notes and example letters from the book—e.g. the letter written from Stanley Pearce to his mother on pages 50-53—students write their own letters, placed into addressed envelopes (some students may have never experienced this) for actual mailing. I would want students to reflect (further conversation and writing) on this process compared to the ease of phone calling, texting, tweeting, chirping, whistling, liking and friending, etc.

7. Transportation—Then and Now. Clearly, communication methods and technology have changed between 1897 and 2014. Modes of transportation have also gone through a bit of a revolution in the same time period. In a similar manner to the T-chart in #5 above, students could chart the modes of transportation experienced by Pearce and Bonds (and all their equipment) as they travelled from Seattle, Washington to Dawson City in the Northwest Territories. Steamship, rowboat, train, horseback, dog sled, foot could all be nearly replaced today by airplane and helicopter. This is where the book’s photographs and maps are more than mere handy references. Using a document camera, I would linger over the photos (as unpleasant as a few are) of the dead horses on pages 48-49, of the 1500 “Golden Stairs” at Chilkoot Pass on page 51, of the hand-built boats on pages 128-129, of the Whitehorse Rapids on pages 62-63, and of the “traffic jam” on the White Pass Trail on pages 42-43. (Of course you and your students will have your own favorites, as well.) Each of these photos would be worthy of a discussion and written reflection. Gold fever was truly a powerful “sickness” if these men were willing to suffer the hardships they endured just to get to the Yukon.

8. Voice–Readers Theater. The letters, telegrams, and diary entries from Pearce and Bond highlighted in #5 above, are not merely important sources of information to be researched, they are essential to the telling of this true adventure. They are the written thoughts, observations, feelings, experiences of Stanley Pearce and Marshall Bond, two very real people. David Meissner has thoughtfully selected, transcribed, and organized these writings to assist Pearce and Bond in the telling of their stories. I believe we owe it to Mr. Pearce and Mr. Bond (and the author) to “hear” their voices by reading at least some the letters and diary entries aloud. This could be done as reader’s theater, with the help of your students to create a “script.” This could include portions of letters, diary entries, and selected parts of the author’s text to serve as the story’s “narrator.” Your students might be interested in using their script performed by students as voice over to a Ken Burns style moving montage of the book’s photographs, with period music accompaniment.

9. Jack London and Robert W. Service. I would be remiss if I didn’t urge you to enrich the already rich content of this book with the novels/short stories (or at least excerpts) of Jack London and the poetry of Robert W. Service. In fact, this book begins with an excerpt from Service’s poem “The Spell of the Yukon.” http://www.poetryfoundation.org will provide you with both his background and access to many of his poems. They are fun to read aloud and provide a poet’s view of the Yukon, the wild times, and the many wild characters who ventured north for gold. Students might want to try their hand at imitating Service’s structure/rhyming scheme with original poems about Pearce, Bond, Dawson City, etc.

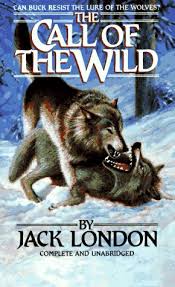

You will discover from Call of the Klondike, Stanley Pearce and Marshall Bond became acquainted with Jack London in Dawson City and even “hung out” with him. In fact, Buck, the canine protagonist of The Call of the Wild, is based on Jack, one of Pearce and Bond’s dogs. (Refer to pages 142-144 for more on this, including a photograph.) A quick visit to http://www.jacklondon.com will give both a brief biography and a list of his written work.

10. Argument—Human “Needs” vs. Environmental Impact, Mineral Extraction—Past and Present, Affect on the Native People of the Northwest Territories, etc. In a section at the end of the book, “Casualties of the Gold Rush,” the author appropriately opens the door for further thinking, research, and writing. The environment and the Native people’s side of the gold rush story are two of the topics, suggested or implied, for students to pursue further. These would make excellent topics for discussion, debate, public speaking, argument/persuasive writing, or even a mock trial.

Visit http://www.bydavidmeissner.com to find out more about David Meissner’s background, books, and articles.

On Another Note—

Check out http://www.goodnaturepublishing.com, a recently discovered site and

an excellent source for cool posters for your classroom.

Coming up on Gurus . . .

Jeff (me) will be reviewing one (or more—I can’t decide) of the following fascinating books: Steve Sheinkin’s The Port Chicago 50:Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights, Into the Unknown: How Great Explorers Found Their Way by Land, Sea, and Air by Stewart Ross (the book’s slip cover unfolds into a map!), or When the Beat Was Born: DJ Kool Herc and the Creation of Hip Hop by Laban Carrick Hill. In the meantime, if reading this or any of our other 134 informative posts has you thinking about professional development in writing instruction during the remainder of this school year, we can help. Whether your focus is on complying with the Common Core writing standards or making students strong writers for life, we can make it happen. Let us design a seminar or series of classroom demo’s to meet your needs at the classroom, building, or district level. We can incorporate any combination of the following: Common Core Standards for writing, the 6 traits, writing strong narrative, exposition, or argument, and the best in literature for young people. Please contact us for details or with questions at any time: 503-579-3034. Thanks for stopping by. Come back—and bring friends. And remember . . . Give every child a voice.